" it is difficult to hear anything other than “I've missed you so much, the phantom's misty tuna brother.” " -Elias d, 1oth grade

Movie watching with subtitles has been increasingly common as streaming services take over television. Many Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ viewers alike have been turning to the permanent enabling of under-screen subtitles because they don’t understand onscreen interactions thanks to impossibly underenunciated dialogue.

When asked, the sample of today’s youth admitted to turning on subtitles during streaming as a force of habit. Bee Ahlers, a 10th grader at OSA said she mainly used them to “help me understand, ‘cause I miss things and get distracted, [but] I don’t think a lot of people my age use subtitles who aren’t hard of hearing”.

Fellow sophomore Declan McMahon, responded similarly: “Everything’s quieter and more mumbly these days. I often [enable subtitles] when I can’t hear what’s being said… and it’s my father’s pet peeve.” This is consistent with the fact that a popular study showed ‘older respondents, such as Generation X and baby boomers,’ were exponentially less likely to watch movies with subtitles enabled. Both Ahlers and McMahon were surprised when told the actual data from the aforementioned study, specifically that around 89% of people, mostly younger, tend to regularly use subtitles.

Some think the answer is simply widespread deafness due to exponentially increasing noise pollution, but what if I told you there was a science of multiple factors working together behind this subtitle conundrum? Why is it that well over half of native English speakers with no hearing conditions claim to need subtitles to understand the content they watch?

The first appearance of subtitles (then called intertitles) occurred in 1903, in Edwin S. Porter’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In the film, dialogue shown as if typed on pieces of paper was inserted between shots for the convenience of the viewer. Most silent films at the time followed suit with this method of expressing the dialogue. Moving into the era of films with sound, the clipped transatlantic accents combined with intricately thought-out microphone placement ensured that written subtitles weren’t missed in cinema. Modern subtitles (under the film) were originally introduced for the purpose of translation for international audiences.

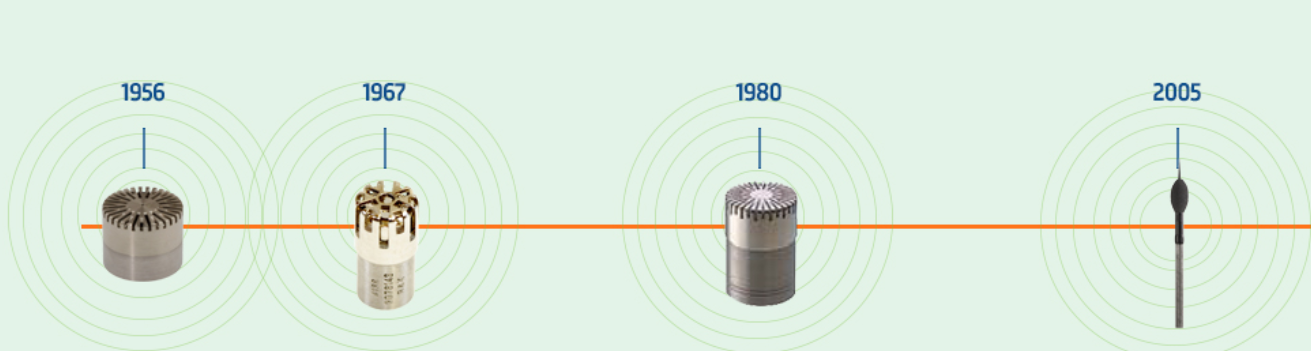

Microphones have gotten better, and smaller since the first ‘talkie’ film in 1927. In today’s industry, a typical sound engineering setup consists of two boom mics and a hidden microphone per actor in the scene, according to Vox. Directly because of this, actors intonations have shifted to more natural, conversational speaking since their microphone not picking up their lines is no longer a concern. In other words, the reason we need subtitles isn’t an issue with the microphones.

When asked, the sample of today’s youth admitted to turning on subtitles during streaming as a force of habit. Bee Ahlers, a 10th grader at OSA said she mainly used them to “help me understand, ‘cause I miss things and get distracted, [but] I don’t think a lot of people my age use subtitles who aren’t hard of hearing”.

Fellow sophomore Declan McMahon, responded similarly: “Everything’s quieter and more mumbly these days. I often [enable subtitles] when I can’t hear what’s being said… and it’s my father’s pet peeve.” This is consistent with the fact that a popular study showed ‘older respondents, such as Generation X and baby boomers,’ were exponentially less likely to watch movies with subtitles enabled. Both Ahlers and McMahon were surprised when told the actual data from the aforementioned study, specifically that around 89% of people, mostly younger, tend to regularly use subtitles.

Some think the answer is simply widespread deafness due to exponentially increasing noise pollution, but what if I told you there was a science of multiple factors working together behind this subtitle conundrum? Why is it that well over half of native English speakers with no hearing conditions claim to need subtitles to understand the content they watch?

The first appearance of subtitles (then called intertitles) occurred in 1903, in Edwin S. Porter’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In the film, dialogue shown as if typed on pieces of paper was inserted between shots for the convenience of the viewer. Most silent films at the time followed suit with this method of expressing the dialogue. Moving into the era of films with sound, the clipped transatlantic accents combined with intricately thought-out microphone placement ensured that written subtitles weren’t missed in cinema. Modern subtitles (under the film) were originally introduced for the purpose of translation for international audiences.

Microphones have gotten better, and smaller since the first ‘talkie’ film in 1927. In today’s industry, a typical sound engineering setup consists of two boom mics and a hidden microphone per actor in the scene, according to Vox. Directly because of this, actors intonations have shifted to more natural, conversational speaking since their microphone not picking up their lines is no longer a concern. In other words, the reason we need subtitles isn’t an issue with the microphones.

Yet, even as microphones have vastly improved, dialogue audibility continues to be an issue. Predictably, the rest of sound engineering software has evolved with microphones. Now we can digitally manipulate sound effects and music as well as the dialogue, and sound mixers have a certain guiding factor when it comes to what audio ultimately makes it to the silver screen. Dynamic range is “the ratio of the largest to the smallest intensity of sound that can be reliably transmitted or reproduced by a particular sound system, measured in decibels,” says Oxford Languages.

Essentially, limited by the intensity of sounds that equipment is able to produce, we as an audience need different volumes assigned to different events to give a sense of scale to the scene. What we hear has to plausibly match up to what we see onscreen for an immersive viewing experience, so we can’t have two people whispering be exactly as loud as a thunderstorm or else the storm loses its sense of scale. Resultantly, when movies follow dynamic range as a guide, it often comes at the cost of some inaudible or even completely lost dialogue. In Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige, for example, a charcter, Borden, reunites with his daughter, but no matter how loud you turn the movie up, it is difficult to hear anything other than “I've missed you so much, the phantom's misty tuna brother.” If the movie hadn’t had the emotionally moving soundtrack, the line more likely would have come across without a problem, but the scene needed emotional weight that couldn’t be provided without musical accompaniment.

The final issue lies in the fundamentals of cinema viewing. The fact is that the majority of movies are designed to be viewed in a surround sound theater, like the high-quality Dolby Atmos sound system outfitted in AMC theaters. When you play something on your TV, the audio has been reduced (downmixed) from up to 128 audio outputs to 2, known as stereo audio. This would explain why we have issues understanding Tom Hardy’s mumbling through a cell phone’s tinny speakers in a bathroom with horrible acoustics.

The combination of all these factors make for some incomprehensible viewing, but you can rest assured that it’s not just your poor hearing. Though it seems bleak, luckily, many TVs and streaming services have started incorporating a built in increased dialogue audibility mode, the latest being Amazon’s “Dialogue Boost'' mid April. So, fingers crossed, it looks like the future of television isn’t going to have to be underamplified conversations spoken in mumble rap.

Essentially, limited by the intensity of sounds that equipment is able to produce, we as an audience need different volumes assigned to different events to give a sense of scale to the scene. What we hear has to plausibly match up to what we see onscreen for an immersive viewing experience, so we can’t have two people whispering be exactly as loud as a thunderstorm or else the storm loses its sense of scale. Resultantly, when movies follow dynamic range as a guide, it often comes at the cost of some inaudible or even completely lost dialogue. In Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige, for example, a charcter, Borden, reunites with his daughter, but no matter how loud you turn the movie up, it is difficult to hear anything other than “I've missed you so much, the phantom's misty tuna brother.” If the movie hadn’t had the emotionally moving soundtrack, the line more likely would have come across without a problem, but the scene needed emotional weight that couldn’t be provided without musical accompaniment.

The final issue lies in the fundamentals of cinema viewing. The fact is that the majority of movies are designed to be viewed in a surround sound theater, like the high-quality Dolby Atmos sound system outfitted in AMC theaters. When you play something on your TV, the audio has been reduced (downmixed) from up to 128 audio outputs to 2, known as stereo audio. This would explain why we have issues understanding Tom Hardy’s mumbling through a cell phone’s tinny speakers in a bathroom with horrible acoustics.

The combination of all these factors make for some incomprehensible viewing, but you can rest assured that it’s not just your poor hearing. Though it seems bleak, luckily, many TVs and streaming services have started incorporating a built in increased dialogue audibility mode, the latest being Amazon’s “Dialogue Boost'' mid April. So, fingers crossed, it looks like the future of television isn’t going to have to be underamplified conversations spoken in mumble rap.