Introduction

With today’s precarious attitude toward immigrants, it is important more than ever to preserve the stories of those who have been impacted by xenophobia. We are celebrating the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht on Nov 8-9. I interviewed my great aunt, Marlene about her memories of fleeing Germany during the Holocaust, stories of my grandma, her sister, and the difficulties she faced with her transition to the U.S. She speaks about the dilemma of leaving one’s home country and her memories of the Nazi’s rise to power.

With today’s precarious attitude toward immigrants, it is important more than ever to preserve the stories of those who have been impacted by xenophobia. We are celebrating the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht on Nov 8-9. I interviewed my great aunt, Marlene about her memories of fleeing Germany during the Holocaust, stories of my grandma, her sister, and the difficulties she faced with her transition to the U.S. She speaks about the dilemma of leaving one’s home country and her memories of the Nazi’s rise to power.

Beginnings

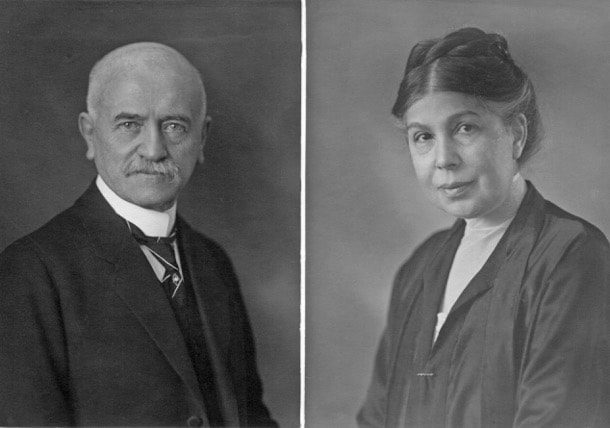

I remember going on house calls with my dad. It was the only way to see him since he was so busy. I remember how big and white his doctor’s apron was. Both he and his father served in the German Medical Corp on the Eastern Front in Russia during World War I. My grandfather held a particularly high rank as the Military Medical Doctor.

We lived in Kurniksburg, now Kalinengrad, a Russian naval base. Kurniksburg is at the Pregal River in East Prussia, once part of Germany. It was bitter cold and dark. First we lived in Schiller Strasse, and later on Louisinalle. I shared a room with my sister Renate. We would sit outside the window and identify types of cars. From my bed, I could see this print of the Mona Lisa on the wall.

When Renate was born, I got shipped to the Roseno’s for the day. They’re the grandparents of Oregon senator Ron Wyden, an old time family friend. I was having such a good time that didn’t want to come home.

I remember going on house calls with my dad. It was the only way to see him since he was so busy. I remember how big and white his doctor’s apron was. Both he and his father served in the German Medical Corp on the Eastern Front in Russia during World War I. My grandfather held a particularly high rank as the Military Medical Doctor.

We lived in Kurniksburg, now Kalinengrad, a Russian naval base. Kurniksburg is at the Pregal River in East Prussia, once part of Germany. It was bitter cold and dark. First we lived in Schiller Strasse, and later on Louisinalle. I shared a room with my sister Renate. We would sit outside the window and identify types of cars. From my bed, I could see this print of the Mona Lisa on the wall.

When Renate was born, I got shipped to the Roseno’s for the day. They’re the grandparents of Oregon senator Ron Wyden, an old time family friend. I was having such a good time that didn’t want to come home.

The first house that Marlene and Renate lived in at 18 Schillerstrasse, past and present

Nazis

Vaguely I remember standing in a dark room in the apartment and being told about Hitler’s rise to power but not knowing what it meant. I was eleven years old.

In 1934, we got our first car, an Adler. My parents had gone on a ski trip to Austria and picked it up on their way back. They ran into some unpleasant Nazis and grew concerned for their safety. They called home to see if they had had any trouble there. They hadn’t, and figured they were safe because Curt was a medalled war veteran. They were advised to leave the car in Berlin and take the train back to Kuniksburg.

You had to be careful what you said, after the Nazis came to power. We had a housekeeper, a seamstress who sewed us new clothes, and someone who came to do our laundry. My mother didn’t learn to cook until we moved to the U.S.

Nazis

Vaguely I remember standing in a dark room in the apartment and being told about Hitler’s rise to power but not knowing what it meant. I was eleven years old.

In 1934, we got our first car, an Adler. My parents had gone on a ski trip to Austria and picked it up on their way back. They ran into some unpleasant Nazis and grew concerned for their safety. They called home to see if they had had any trouble there. They hadn’t, and figured they were safe because Curt was a medalled war veteran. They were advised to leave the car in Berlin and take the train back to Kuniksburg.

You had to be careful what you said, after the Nazis came to power. We had a housekeeper, a seamstress who sewed us new clothes, and someone who came to do our laundry. My mother didn’t learn to cook until we moved to the U.S.

Curt was the Director of a government funded children’s hospital. When Hitler came to power, Jews were forbidden from holding government funded positions. My father returned from vacation to be banned from even returning to his office. Then he opened a private practice to properly serve Jewish children in the community.

I remember classmates moving away. Kids started giving Renate trouble in school so they took her out. Some girls wore the BDM uniform, the girl’s version of Hitler Youth. Parents started talking about leaving Germany. Curt’s father said, “A good German doesn’t leave just because he doesn’t like the government.” One of his former students, now the head of a hospital in Athens, offered him a position. He refused, saying that if they left Germany they would leave Europe altogether and for good.

When we visited Uncle Otto in Brussels he offered my parents money to go to the states. My mother and her sister, Mimo, cut their hair short and tried on lipstick. Curt told them not to come back into the house until they had wiped that silly stuff off their lips. It was during that trip that Uncle Otto convinced them to leave Germany.

I remember classmates moving away. Kids started giving Renate trouble in school so they took her out. Some girls wore the BDM uniform, the girl’s version of Hitler Youth. Parents started talking about leaving Germany. Curt’s father said, “A good German doesn’t leave just because he doesn’t like the government.” One of his former students, now the head of a hospital in Athens, offered him a position. He refused, saying that if they left Germany they would leave Europe altogether and for good.

When we visited Uncle Otto in Brussels he offered my parents money to go to the states. My mother and her sister, Mimo, cut their hair short and tried on lipstick. Curt told them not to come back into the house until they had wiped that silly stuff off their lips. It was during that trip that Uncle Otto convinced them to leave Germany.

Departure

What was most traumatic was not being able to take my Kate Kuzer doll.

Renate and Suzie were considered fragile so they were sent to a children’s camp while the family packed. When they returned, they were brought straight to Frankfurt. I was treated more aloof by both my parents.

My parents needed proof that they had a guaranteed job so that they would not burden the American taxpayers. One of my mother’s cousins was a professor at the University of Rochester and he was able to secure Curt a non-paying research position at the medical school there. In that time, he would have to learn English so that he could pass certification exams and begin practicing. We were able to bring a lot of objects, but not money. My father bought an x-ray machine in anticipation of work in the U.S.

We sailed aboard the Berengaria. As we ate our first meal aboard the ship, I remarked how smooth sailing it was. It turned out we hadn’t left yet. I shared a room with a very strict nurse. She’d slap me to wake up even when I suffered from motion sickness. Renate and Curt didn’t get seak sick, so they’d go on deck together. They had grapefruit, which was very rare in Germany. Once, I accidentally put salt instead of sugar on my grapefruit and it set off my seasickness.

What was most traumatic was not being able to take my Kate Kuzer doll.

Renate and Suzie were considered fragile so they were sent to a children’s camp while the family packed. When they returned, they were brought straight to Frankfurt. I was treated more aloof by both my parents.

My parents needed proof that they had a guaranteed job so that they would not burden the American taxpayers. One of my mother’s cousins was a professor at the University of Rochester and he was able to secure Curt a non-paying research position at the medical school there. In that time, he would have to learn English so that he could pass certification exams and begin practicing. We were able to bring a lot of objects, but not money. My father bought an x-ray machine in anticipation of work in the U.S.

We sailed aboard the Berengaria. As we ate our first meal aboard the ship, I remarked how smooth sailing it was. It turned out we hadn’t left yet. I shared a room with a very strict nurse. She’d slap me to wake up even when I suffered from motion sickness. Renate and Curt didn’t get seak sick, so they’d go on deck together. They had grapefruit, which was very rare in Germany. Once, I accidentally put salt instead of sugar on my grapefruit and it set off my seasickness.

Epilogue

Kurniksburg became Kaliningrad. One of my father’s friends advised against us visiting because it was Russian now. We wouldn’t recognize anything. It had been flattened by bombs. Renate visited in 1997 and couldn’t locate any of the streets we had lived on. We were incredibly fortunate that almost all of our close family members got out.

The story of how my grandparents, Omama and Opapa, got out, is mysterious and brief. It is unclear how they were able to leave so late. Goerdeler went to the train station to see them off. He gave them a large bunch of roses. Goerdeler had been the local mayor before the Nazis came to power. Later, he was part of the plot to overthrow Hitler. My grandparents stayed in Cuba for two years as my father worked on obtaining citizenship papers for them.

Even after my parents were kicked out of their houses, their friends had their professions and belongings confiscated, and they were forced to take in others, my grandparents refused to leave. They too believed that a good German does not leave. My father tried to get them out, but couldn’t obtain passports. In the very last minute, they were able to book a sealed train through Lisbon to a ship to Cuba. My grandma broke her arm on the ship.

My parents thought it would be too emotional for me to go to the train station in New York City to pick up my grandparents. I met them at the house. My grandma said, “don’t kiss me! You’re wearing lipstick.” That was the last time I interacted with her for quite a while.

Kurniksburg became Kaliningrad. One of my father’s friends advised against us visiting because it was Russian now. We wouldn’t recognize anything. It had been flattened by bombs. Renate visited in 1997 and couldn’t locate any of the streets we had lived on. We were incredibly fortunate that almost all of our close family members got out.

The story of how my grandparents, Omama and Opapa, got out, is mysterious and brief. It is unclear how they were able to leave so late. Goerdeler went to the train station to see them off. He gave them a large bunch of roses. Goerdeler had been the local mayor before the Nazis came to power. Later, he was part of the plot to overthrow Hitler. My grandparents stayed in Cuba for two years as my father worked on obtaining citizenship papers for them.

Even after my parents were kicked out of their houses, their friends had their professions and belongings confiscated, and they were forced to take in others, my grandparents refused to leave. They too believed that a good German does not leave. My father tried to get them out, but couldn’t obtain passports. In the very last minute, they were able to book a sealed train through Lisbon to a ship to Cuba. My grandma broke her arm on the ship.

My parents thought it would be too emotional for me to go to the train station in New York City to pick up my grandparents. I met them at the house. My grandma said, “don’t kiss me! You’re wearing lipstick.” That was the last time I interacted with her for quite a while.