"I invite each reader to be a fly on the wall as we discuss how a city recreates itself overtime, even when the rebirth looks similar to that of a death." - Elena Ruiz

When I first entered Oakland City Hall, my nerves were jumping frantically. I was twenty minutes early, well read on the city council member I would be interviewing, and more importantly, I had dressed appropriately as to set a good impression. Lynette McElhaney was the city council member in which I needed to impress, as she was going to help me better understand the history of gentrification in Oakland. When she came out to meet me, the nerves immediately melted away as her warm spirit and familiar character invited me to her office. She was the real deal, and if there was anyone who I needed to learn about gentrification from, it was her. From a conversation about the districts of Oakland, to the history of Oakland, and the ways in which Oakland has transformed and will continue to transform, we examined it all. I invite each reader to be a fly on the wall as we discuss how a city recreates itself overtime, even when the rebirth looks similar to that of a death.

Elena Ruiz: So you are the leader of District 3, can you please explain what the different districts of Oakland are?

Elena Ruiz: So you are the leader of District 3, can you please explain what the different districts of Oakland are?

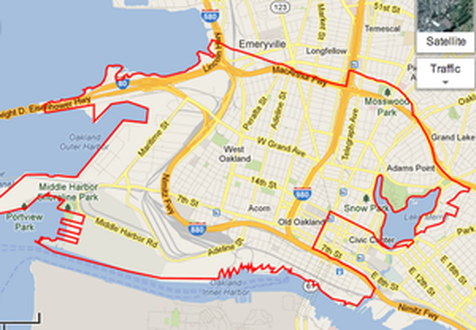

District 3 of Oakland, CA

District 3 of Oakland, CA Lynette McElhaney: It [the measures of the district] shifts every ten years with the census, and how it will change in the next go round will be different because it will be done by a commission [a measure that I did not support]. The charter requires that the districts are roughly the same in population, not geography. The wisdom up until now has been to draw the district lines in such a way that every district has to address affluent constituents as well as poor ones. There was a push, it seems to me, I think it goes back to the late 70s, early 80s to stop districting poor communities. Such as gerrymandering the community so that it’s all poor, because what you’ll end up with in that case is leaders who have no real leverage on the council. You know what I mean? If you have poor people on the council who are representing wealth, it becomes an imbalance because poor people do not turn out in the same way. So inequity cuts across all kinds of ways in which we live and it shows up in how we participate as well and that’s something that we as organizers push around; how do you empower people, how do you get poor people because it requires so much more organizing, education, and lifting up? Affluent communities grow up with the presumption of government participation, their education is better, there’s a whole bunch of stuff.

So District 3, I call it the Heart and Soul of the Town because it goes from where the Bay touches ground on our shores, the furthest point West that you can get to. From the Bay to Lake Merritt, from Jack London, from the Estuary up to the Mac Arthur freeway, and West Mac Arthur Boulevard. A portion of that northern line is that actual street [MacArthur Boulevard] roughly goes along where the freeway overpasses, so it’s a weird jigger, and you end up making those kind of compromises because you’re trying to get to where we each a have about 62,000 people. District 7 is the largest land mass, but it’s the least dense of the population of the development areas. Districts 1 and 3 are the most dense, lots of multi families, lots of condos, high rises, that kind of stuff.

This district that I represent, houses the historic community, West Oakland, where under redlining, there’s sort of an inverse gentrification, it was the only place black people could live. We were on the reservation of West Oakland, which has previously been portuguese and other immigrants [land] and is now reconstituting itself as a multi cultural place. It was never ever all exclusively black, it was predominately black, and because of that we saw a lot of irregular land use decisions, allowing and permitting industrial uses next to residential uses, not good land practice. The people were not given a lot of voice and when the federal government in response to civil rights gangs wanting to make it possible for people to suburbanized themselves away from blackness, freeways and transit systems came through and our predecessors and government accepted that federal money and allowed for example B.A.R.T to rip up African American middle class communities and displace hundreds of homes. And the freeway, the 9-80 which is still the most under—one of the most under utilized freeways in the country, but it demolished something like 1000-1200 homes to make a conductor between freeways, so that people could literally bypass Oakland when they wanted to contain blackness in Oakland, and let the suburbs be pristine.

So District 3, I call it the Heart and Soul of the Town because it goes from where the Bay touches ground on our shores, the furthest point West that you can get to. From the Bay to Lake Merritt, from Jack London, from the Estuary up to the Mac Arthur freeway, and West Mac Arthur Boulevard. A portion of that northern line is that actual street [MacArthur Boulevard] roughly goes along where the freeway overpasses, so it’s a weird jigger, and you end up making those kind of compromises because you’re trying to get to where we each a have about 62,000 people. District 7 is the largest land mass, but it’s the least dense of the population of the development areas. Districts 1 and 3 are the most dense, lots of multi families, lots of condos, high rises, that kind of stuff.

This district that I represent, houses the historic community, West Oakland, where under redlining, there’s sort of an inverse gentrification, it was the only place black people could live. We were on the reservation of West Oakland, which has previously been portuguese and other immigrants [land] and is now reconstituting itself as a multi cultural place. It was never ever all exclusively black, it was predominately black, and because of that we saw a lot of irregular land use decisions, allowing and permitting industrial uses next to residential uses, not good land practice. The people were not given a lot of voice and when the federal government in response to civil rights gangs wanting to make it possible for people to suburbanized themselves away from blackness, freeways and transit systems came through and our predecessors and government accepted that federal money and allowed for example B.A.R.T to rip up African American middle class communities and displace hundreds of homes. And the freeway, the 9-80 which is still the most under—one of the most under utilized freeways in the country, but it demolished something like 1000-1200 homes to make a conductor between freeways, so that people could literally bypass Oakland when they wanted to contain blackness in Oakland, and let the suburbs be pristine.

So that’s sort of the backdrop that I give you to say, well how do we really understand gentrification in the context of when African Americans migrated here? For work, from the South, from segregation, it was not their intent to move into California segregated communities, it was not their intent to bump into American apartheid and be left on the reservation of West Oakland, but as oppressed people do, you make the best of a bad situation. They created social institutions, social halls, social clubs, night clubs, restaurants, they created entrepreneurial opportunities, they built their homes and housing, and they made the most of being paid less than their white counterparts while they worked as pullman porters, as long shoreman, as post office workers. They created a very rich living and social existence from which people take a great deal of pride, but they also suffered a great deal in the segregation, California segregation. To the point where police abuse was rampant so rampant and so egregious it led to the formation and founding of the Black Panther Party 50 years ago in West Oakland.

It’s hard for me because sometimes I listen to people and we have these, like these glamorous pasts “West Oakland was deep, we had this park, and we did this, and Bill Russell came out of McClimans.” There’s all this celebration of black culture and identity glossing over the fact that people were paid half the wages of white counterparts doing the same thing. The fact that properties were redlined, you couldn’t get loans, those who owned homes had to pay for them in cash, [black residents] couldn’t get those properties adequately insured or they were paying too much for insurance, always subject to City Hall knocking down your neighbors house building projects, concentrating poverty in your neighborhood. There was a whole bunch of stuff going on and I don’t find that there was ever a period where black people could be like “Oh yeah it was so good, you know it was so good right there” well it wasn’t good. The Panthers were not a black pride organization that just came like a cultural exchange program. You know like “Oh yeah we the Black Panthers we’re gonna teach you all of our North American African American dances, art, and music and take that on the show to go share our gifts with the rest of the European world because we’re just so cool like that right here.” No it wasn’t like that.

My background in community development said this. I would look at a community and I’ve worked in communities very similar to West Oakland, where black people would largely rent, where homeownership rates were low, where schools were underperforming, where environmental harms were great because of land use decisions that permitted industrial uses in residential communities, and my job was to bring in positive reinvestment. How do I get banks to lend in this community so that people who are renting here, who love it here can own here and own their destiny, and not have to be subject to the whims of a landlord? How do we get a grocery store when you can’t get a grocery store if banks won’t lend the capital the money, the cash flow money, because inventory is expensive at a grocery store? So I need a million dollars just to put product on the shelf before anybody comes and buys a soda for a dollar. I need this kind of cash flow. Well banks won’t sell to certain zip codes or where they don't see a certain household income in the neighborhood. So for me, bringing in more affluent families into deeply impoverished segregated communities is called positive community economic development or community reinvestment.

Urban pioneers is one of the names that they started calling white people who migrated into these communities, artists living in warehouses doing all of the unconventional things. When they start showing up without incentives through redevelopment and other things, that first wave is actually embraced and welcomed by most neighbors. “Oh yeah we’ve had that dilapidated warehouse over there it’s just been an eyesore and people have been dumping on it for years. It’s great that Steve and Becky have moved on in and are making it a nice place and they’re cleaning up the street.

From a public health perspective it’s good because you begin to deconcentrate poverty. High concentration of poverty is not good for people. That in and of itself is not a bad thing, and then when you start talking about well how are people being displaced, well what does that mean when rents are rising and is that displacing families or...? You know it just gets so complicated. It gets so complicated for me and I don’t want to ramble, but you know I recognize that there’s a lot of pain involved in America’s economic decisions being at one point no money could come into the urban core, everything was driven to the suburbs, we called that white flight.

For thirty years people decried well how do you get cities like Oakland to thrive in the recognition of white flight? You can’t make white folks stay, you can’t make people of affluence stay in these communities when they’ve decided to go, and when they left they took the tax pays, the took the economics that banks desire. So malls like Eastmont dry up because eventually stores can’t get the insurance, can’t get the capital that they need to stay in the urban marketplace. So they shut down that store and they go to where the banks and the insurers want them to be, or where their demographic says that they should go, where the incomes are higher and the crime rates are lower. So then you have a mall that shutters and you have a community that's left saying “the city should do something”, well what should the city do? Cities aren't set up to be private businesses. So you begin to try to do what cities do so that you can foster and attract private capital.

From a public health perspective it’s good because you begin to deconcentrate poverty. High concentration of poverty is not good for people. That in and of itself is not a bad thing, and then when you start talking about well how are people being displaced, well what does that mean when rents are rising and is that displacing families or...? You know it just gets so complicated. It gets so complicated for me and I don’t want to ramble, but you know I recognize that there’s a lot of pain involved in America’s economic decisions being at one point no money could come into the urban core, everything was driven to the suburbs, we called that white flight.

For thirty years people decried well how do you get cities like Oakland to thrive in the recognition of white flight? You can’t make white folks stay, you can’t make people of affluence stay in these communities when they’ve decided to go, and when they left they took the tax pays, the took the economics that banks desire. So malls like Eastmont dry up because eventually stores can’t get the insurance, can’t get the capital that they need to stay in the urban marketplace. So they shut down that store and they go to where the banks and the insurers want them to be, or where their demographic says that they should go, where the incomes are higher and the crime rates are lower. So then you have a mall that shutters and you have a community that's left saying “the city should do something”, well what should the city do? Cities aren't set up to be private businesses. So you begin to try to do what cities do so that you can foster and attract private capital.

Capital markets are still really racist and there’s not a lot of oversight for them. They still are very racist and they still are very discriminatory to low income communities. What’s insane about it is their own economic data will tell you that poor people spend more, poor people actually have less lower default rates. It’s not a question of is there money here. That part saddens me. These economists will look and see how much money, for example, is being spent at McDonalds and they will know that there’s enough disposable income within a community that you could support an Applebee's, Applebee’s won’t come. And they know, because they do all of these econometrics, so they know all of these people from these poor zip codes are going over to Alameda, buying at Applebee’s and they will serve them. They’ll take their money at Alameda, but they won’t permit a franchise to come to Oakland, even when you have an entrepreneur who wants one. The franchise will say no we’re not going to build one, household incomes aren’t high enough in this area, we’re afraid of insurance claims, or it just has a bad rep. This residential move to Oakland is really interesting because I think we show up differently than some of the other parts of the country.

Gentrification tends to feel the same in every community, but it’s really driven by different things. Like Portland is experiencing a different kind of wave even though the yoga shops, the coffee shops, they all feel the same. So when do you want to start gentrification, when do you want to start the story? Do you want to start the story with all of those black families that lived in South Berkeley who got pushed out by Berkeley students and Berkeley professors who wanted to buy those beautiful homes in South Berkeley? Or do you wanna look at the fact that once those people moved black people from South Berkeley into North Oakland, and then North Oakland that had been predominately white, was now predominantly black. We have these beautiful grow communities of North Oakland black people, who let North Oakland have this church, and Lois the Pie Queen, you know the Black Panthers at Merritt College which is now the research center for Children’s Hospital, like all of that stuff that was such a robust black community, when we’re crying about gentrification, was that wave pushed? Where does it start?

Gentrification tends to feel the same in every community, but it’s really driven by different things. Like Portland is experiencing a different kind of wave even though the yoga shops, the coffee shops, they all feel the same. So when do you want to start gentrification, when do you want to start the story? Do you want to start the story with all of those black families that lived in South Berkeley who got pushed out by Berkeley students and Berkeley professors who wanted to buy those beautiful homes in South Berkeley? Or do you wanna look at the fact that once those people moved black people from South Berkeley into North Oakland, and then North Oakland that had been predominately white, was now predominantly black. We have these beautiful grow communities of North Oakland black people, who let North Oakland have this church, and Lois the Pie Queen, you know the Black Panthers at Merritt College which is now the research center for Children’s Hospital, like all of that stuff that was such a robust black community, when we’re crying about gentrification, was that wave pushed? Where does it start?

ER: That’s the big question.

LM: Right that’s the big question because people feel the pain now, but there are really like economic refugees, it wasn’t white pioneers moving to West Oakland because West Oakland was great, the white pioneer who did that was Bruce Beesley, he was an artist and moved into an industrial land because he didn’t want nobody messin’ with him when he built big sculptures, and you know that in a poor community they ain’t calling the police on you, you can do all kinds of crazy stuff, blow torch stuff, ain’t nobody sayin nothin’. So he was the urban pioneer, but after that you get a whole bunch of people who after that they can’t afford to live where they wanna be.

ER: I guess in the sort of wave of gentrification that we’re experiencing now, I think a lot of people assume that it’s because of this tech industry that’s happening in San Francisco, but I feel like it’s almost a cycle that just repeats itself.

Tech companies within the Tenderloin District of San Francisco

Tech companies within the Tenderloin District of San Francisco LM: In some ways that’s true. Oakland missed two waves of the tech boat. People weren’t coming because they could live where they wanted to be. They moved to Hayward, South San Francisco, they were all down in the peninsula where there was all this excess inventory. Now you get these people because tech moved to Downtown San Francisco. Willie Brown was apart of attracting it into San Francisco. Why? Because the tax base in San Francisco was decimated. Black folks were leaving San Fransisco already before the tech. When Willie Brown becomes mayor, he’s talking about people are calling San Francisco the armpit of the Bay and he said this was once a grand and glorious city, now it’s dirty, we just have homeless people everywhere, we’ve become a magnet for social services and non profits, we have all these empty store fronts and we can’t get anything done here. If we don’t have a tax base how are we going to take care of schools, roads, and public parks? We’re an old city and we have to have people taking care of stuff. So he’s like what can I do? He starts talking to people and he’s like, how bout a campus downtown, we can practically give you this building. Because the owner doesn’t want it, and it’s an eyesore, and it’s costing me a lot of money because police have to keep coming and putting out fires, it’s an empty building, you want it? Then I think Twitter or somebody takes over and it grows from there. Don’t quote me on which business went first. I don’t want to exaggerate the story, but there was that wave and then the economics come and they by pass all these poor people who haven’t been served for three generations.

When I look at Oakland, I have African American elders who talk to me about a Downtown, now mind you, remember I told you people get nostalgic for the past. They don’t wanna tell you about the downtown when they couldn’t come into Emporium Capwell or J Malavich when they wouldn’t let black women try on furs. That’s part of Oakland’s history too, but they’re nostalgic for it. They remember when there were movie theatres and the Fox and the Paramount was for movies and for plays, and orchestra, and when you came to shop in Downtown honey, you came Sunday dressed. Your children were in their little shiny vinyl shoes and penny loafers, and loafers, and gloves honey, you see them old pictures. The women wear gloves to go shopping, that kind of stuff and people tell you about that and they’re sad that we don’t have a mall in Downtown and they want it back.

Then I have a whole wave of young people who grew up without the job, without the resources, after AT&T closed, after the airport laid off all of their baggage handlers, after the army bases closed and we don’t have a lot of blue collar shoppers, after we closed the bases in Alameda and here so we don’t see navy boys running Downtown shopping at the De Lauer’s [A newsstand in Downtown Oakland].

After all of that you have all of these young people who grew up after Loma Prieta [An earthquake in 1989] all they know is a greedy, dirty, nasty, city, and they see somebody bring in a high end restaurant and they’re like oh it’s gentrification, you’re catering to rich people, and it’s like is it gentrification when nobody’s been displaced and you have new investment going into derelict spaces? What do we call that? I see people ciphering in front of Rudy’s. When the city built out Rudy’s, I mean built out the Fox and those retail spaces they couldn’t give them away. Couldn’t give them away. The condos Downtown were—here in the Uptown there’s a forest city project, you now see the ice cream store on one end and that fancy new coffee shop, that things been built up for 15 years and nobody wants retail spaces. It was built for retail and nobody came, is that gentrification?

They say over the last 10 years we’ve lost 25% of the African American population here. Majority of those people left not because they were priced out. They left to move to Antioch and Castro Valley where the schools were better, where they felt they could get more for their money, and they could live the american dream. They didn’t wanna be stuck in a community riddled with violence, crack, they wanted better. They wanted to be fully invested in the american dream.

ER: So do you think that with this whole situation of African American people being moved out of Berkeley, is that what sort of created this diversity that Oakland now has and is now experiencing [because Oakland was not always super diverse]?

After all of that you have all of these young people who grew up after Loma Prieta [An earthquake in 1989] all they know is a greedy, dirty, nasty, city, and they see somebody bring in a high end restaurant and they’re like oh it’s gentrification, you’re catering to rich people, and it’s like is it gentrification when nobody’s been displaced and you have new investment going into derelict spaces? What do we call that? I see people ciphering in front of Rudy’s. When the city built out Rudy’s, I mean built out the Fox and those retail spaces they couldn’t give them away. Couldn’t give them away. The condos Downtown were—here in the Uptown there’s a forest city project, you now see the ice cream store on one end and that fancy new coffee shop, that things been built up for 15 years and nobody wants retail spaces. It was built for retail and nobody came, is that gentrification?

They say over the last 10 years we’ve lost 25% of the African American population here. Majority of those people left not because they were priced out. They left to move to Antioch and Castro Valley where the schools were better, where they felt they could get more for their money, and they could live the american dream. They didn’t wanna be stuck in a community riddled with violence, crack, they wanted better. They wanted to be fully invested in the american dream.

ER: So do you think that with this whole situation of African American people being moved out of Berkeley, is that what sort of created this diversity that Oakland now has and is now experiencing [because Oakland was not always super diverse]?

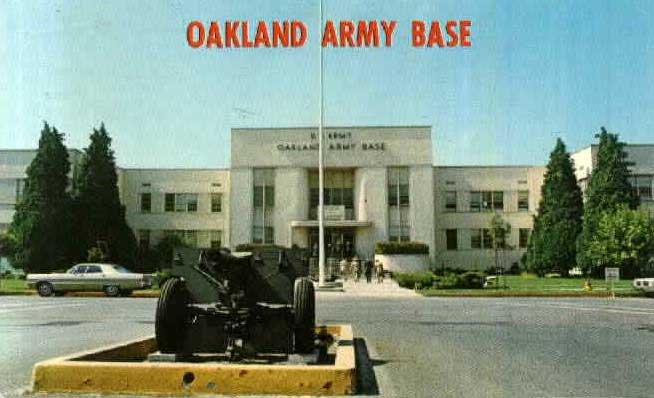

LM: No, the war industry. Black people were migrating to California, that goes all the way back to the thirties, but the biggest push in the area in terms of black presence comes from WWII. People come here to work in the shipyards, to work on the war industries, to work in the car—you know Oakland had automobile industries here, it was considered the Detroit of the West. So once there were jobs that were gonna pay above sharecropper wages in the South, people brought their families out. Whole families migrated from the South. Talking about displacement, the clan was a major displacement operation. People were like oh hell, we need to go west or north. Wilkerson’s book The Warmth of Other Suns--people left family and land, and familiarity for safety, educational opportunities, and economic opportunities.

The military was a major part, we had major military bases here, Treasure Island, Oak Knoll was a major naval outpost here in East Oakland Hills, we had Alameda Naval Air Station, we had the Oakland Army Base was a major place for army deployments. Because they had started integrating the military in the fifties, that was a major push for Oakland in terms of attracting black people here and then black people coming from the South, from the East Coast where it was cold and saying god the weather is good here and we have social mobility. They were making good money relative to the poverty wages black people paid elsewhere, so they made their lives in the bay. They brought their culture, and their music, and the Blues, and Funk, and the Gospel, and the built churches, those churches began to have social impact. You think about early church work from Allen Temple to do economic development or Center of Hope building up schools in the 80’s 90’s like always chasing the american dream of being fully franchised, and then America’s economics change. AT&T lays off people, it's elsewhere. Safeway stops manufacturing in Oakland, moves their plants down to the Central Valley. White flight is a real thing. What frustrates me about this current—because I can have this conversation about rising rents, gentrification, I can do that, but since you wanna know a little bit more about how complex this is.

The military was a major part, we had major military bases here, Treasure Island, Oak Knoll was a major naval outpost here in East Oakland Hills, we had Alameda Naval Air Station, we had the Oakland Army Base was a major place for army deployments. Because they had started integrating the military in the fifties, that was a major push for Oakland in terms of attracting black people here and then black people coming from the South, from the East Coast where it was cold and saying god the weather is good here and we have social mobility. They were making good money relative to the poverty wages black people paid elsewhere, so they made their lives in the bay. They brought their culture, and their music, and the Blues, and Funk, and the Gospel, and the built churches, those churches began to have social impact. You think about early church work from Allen Temple to do economic development or Center of Hope building up schools in the 80’s 90’s like always chasing the american dream of being fully franchised, and then America’s economics change. AT&T lays off people, it's elsewhere. Safeway stops manufacturing in Oakland, moves their plants down to the Central Valley. White flight is a real thing. What frustrates me about this current—because I can have this conversation about rising rents, gentrification, I can do that, but since you wanna know a little bit more about how complex this is.

We came to Oakland because there was a promise embedded in Oakland. It was a place where Walter Hawkins was singing “Oh Happy Day” and Sly and the Family Stone… people got attracted to this place because power of concentration and people believing in the dream. Once the Black Panthers set it off people were all coming here. You know you get the first— I believe Lionel was the first African American mayor in the West Coast, if not the first then the second. This is falling on a wave of these northern cities that are now finding political presence because we’ve concentrated as we move from the south and you move into spaces where you can leverage the conversation differently than you could in the South where the clan was just ruthless and reigning. So the Panthers actually helped get Lionel Wilson elected and he was a judge so he comes from affluence. Today the conversation is this: When we built up for a city nobody was renting but people of color because white folks still wouldn’t come, the social experiment of trying to deconcentrate poverty, bring affluence Downtown, it didn’t come, so when they start moving into those places, is that gentrification? Or when you have a black person who makes a six figure income buy a victorian in West Oakland, is that gentrification? They clearly want to be in a black dynamic, raise their kids in a black dynamic. Do you consider them gentrifiers because they’re not poor?

ER: We never put a definition to what a gentrifier is and who that is. We just assume that it’s this sort of only racial aspect of the “white man” running out the black people.

LM: Right and the white population in Oakland hasn’t shifted that much. It’s up, but you know what’s really up is Hispanic. When I looked at the ABAG projections, I don’t have them in front of me so I don’t want to misquote, but it was really amazing. That’s why I’m telling you people aren’t having the real conversation. I asked ABAG to show me the real demographics. Yes we’ve lost 25% but in that 25% it was middle class. The percentage of poor black people in Oakland is up by 1%. That part I remember, we actually increased poverty. So I wanted the demographers to tell me was that attracting poor people into the city or was it middle class people losing income and becoming poor? What was that 1%, can we dig into the data more? They didn’t give me back the data.

The other thing that I noticed is that when you look at our census you see black people leaving Oakland and you see the increase in Contra Costa, but when blacks move to— the first two waves of black people moving into that county, into Antioch, Oakley, they’re not poor, they’re buying houses. This last wave is people who are being priced out and section 8 is no longer being accepted and stuff. You’re getting a wave of core black and brown people into Contra Costa now. So when people are like we’ve lost 25% of the black people therefore we need to build more affordable housing you’re making the assumption that the people who left needed affordable housing. Some did, most didn’t. They bought a big car, and a big house, and decided to add two hours to their work day, they made that choice. A lot of my friends did.

ER: So the question that I have now is when you have this community that is totally assuming one thing [because we’re not necessarily educated on the actual facts of how Oakland has transitioned over this time] how do you reach out to that community in order to educate them about that, but also in order to get an uneducated community involved in these politics and what’s happening?

LM: Tell me honey, can you help me?

ER: Yes!

LM: I think there’s two things, there is the need for us to think about the broken economy and what frustrates me is that we’re not having that conversation. The economic pain that we are all experiencing is very, very real. Very real. The pain of displacement— let’s take that entire wave of black property owners due to foreclosure and shenanigans with the mortgage market. There’s a story to be told there about racial injustice that’s not really being told and how it disproportionately impacted communities of color, for real. And I’m not talking about the abject poor I’m talking about people who had worked, saved, invested on homes, and got tricked out of that investment on scrupulous deals. There’s a story there and so when people are screaming at me about gentrification, I get the pain. To acknowledge yes the economy is shifting, yes we’re seeing more affluent people move into urban communities, yes capital markets are making that decision today where they refused to refused to make that decision 20 years ago and the capital markets aren’t working with me.

I’m challenging everybody, smart people, they’re way smarter than me. I’m busting up myths. Now that I’m in this seat, there’s a lot of myths. They say it’s not a myth. You probably have learned in your high school econ class that supply and demand are the things that drive price in the market place. And they’ve told you that where there is a demand, ingenuity and creativity, where there is no artificial barriers in the marketplace, that supply will meet demand. So I said to some people, very smart people, and I said I want you guys to help me with something. They started telling me that my price crisis in Oakland was tied to my lack of supply and what I needed to do-and you’ll hear this as part of the answer for gentrification- is we have to build way more housing units. We’re not meeting the demand for market rate, and because we’re not meeting the demand for market rate, these market rate desires are moving into these existing substandard units where they can afford to fix them up and that’s putting incentives on landlords to displace poor people. Makes sense to you and I, yeah.

There’s only one apartment on the street, your mama had it, somebody with more money wanted it, and they kept talking to your landlord till the landlord said we’re not going to renew your lease. Nothing you did wrong, really nothing that the rich person or the more affluent person who’s not rich who can’t afford to live in San Francisco, where they really wanna be, they didn’t do nothing wrong. They’re like I have 2,000 dollars a month to spend on rent, my 2,000 does not buy me anything in San Francisco so if you ever get a unit please know that I will pay you 2,000 dollars a month, Your mom is like I can pay 1,100 dollars a month and that used to be good enough for you, but now the landlord is like hey my bills are rising, I’m getting older, I want to make my retirement plush, I need that 2,000 I don’t need that 1,100. There’s really no bad actors in here. Just everybody trying to make this crazy economy work.

ER: We never put a definition to what a gentrifier is and who that is. We just assume that it’s this sort of only racial aspect of the “white man” running out the black people.

LM: Right and the white population in Oakland hasn’t shifted that much. It’s up, but you know what’s really up is Hispanic. When I looked at the ABAG projections, I don’t have them in front of me so I don’t want to misquote, but it was really amazing. That’s why I’m telling you people aren’t having the real conversation. I asked ABAG to show me the real demographics. Yes we’ve lost 25% but in that 25% it was middle class. The percentage of poor black people in Oakland is up by 1%. That part I remember, we actually increased poverty. So I wanted the demographers to tell me was that attracting poor people into the city or was it middle class people losing income and becoming poor? What was that 1%, can we dig into the data more? They didn’t give me back the data.

The other thing that I noticed is that when you look at our census you see black people leaving Oakland and you see the increase in Contra Costa, but when blacks move to— the first two waves of black people moving into that county, into Antioch, Oakley, they’re not poor, they’re buying houses. This last wave is people who are being priced out and section 8 is no longer being accepted and stuff. You’re getting a wave of core black and brown people into Contra Costa now. So when people are like we’ve lost 25% of the black people therefore we need to build more affordable housing you’re making the assumption that the people who left needed affordable housing. Some did, most didn’t. They bought a big car, and a big house, and decided to add two hours to their work day, they made that choice. A lot of my friends did.

ER: So the question that I have now is when you have this community that is totally assuming one thing [because we’re not necessarily educated on the actual facts of how Oakland has transitioned over this time] how do you reach out to that community in order to educate them about that, but also in order to get an uneducated community involved in these politics and what’s happening?

LM: Tell me honey, can you help me?

ER: Yes!

LM: I think there’s two things, there is the need for us to think about the broken economy and what frustrates me is that we’re not having that conversation. The economic pain that we are all experiencing is very, very real. Very real. The pain of displacement— let’s take that entire wave of black property owners due to foreclosure and shenanigans with the mortgage market. There’s a story to be told there about racial injustice that’s not really being told and how it disproportionately impacted communities of color, for real. And I’m not talking about the abject poor I’m talking about people who had worked, saved, invested on homes, and got tricked out of that investment on scrupulous deals. There’s a story there and so when people are screaming at me about gentrification, I get the pain. To acknowledge yes the economy is shifting, yes we’re seeing more affluent people move into urban communities, yes capital markets are making that decision today where they refused to refused to make that decision 20 years ago and the capital markets aren’t working with me.

I’m challenging everybody, smart people, they’re way smarter than me. I’m busting up myths. Now that I’m in this seat, there’s a lot of myths. They say it’s not a myth. You probably have learned in your high school econ class that supply and demand are the things that drive price in the market place. And they’ve told you that where there is a demand, ingenuity and creativity, where there is no artificial barriers in the marketplace, that supply will meet demand. So I said to some people, very smart people, and I said I want you guys to help me with something. They started telling me that my price crisis in Oakland was tied to my lack of supply and what I needed to do-and you’ll hear this as part of the answer for gentrification- is we have to build way more housing units. We’re not meeting the demand for market rate, and because we’re not meeting the demand for market rate, these market rate desires are moving into these existing substandard units where they can afford to fix them up and that’s putting incentives on landlords to displace poor people. Makes sense to you and I, yeah.

There’s only one apartment on the street, your mama had it, somebody with more money wanted it, and they kept talking to your landlord till the landlord said we’re not going to renew your lease. Nothing you did wrong, really nothing that the rich person or the more affluent person who’s not rich who can’t afford to live in San Francisco, where they really wanna be, they didn’t do nothing wrong. They’re like I have 2,000 dollars a month to spend on rent, my 2,000 does not buy me anything in San Francisco so if you ever get a unit please know that I will pay you 2,000 dollars a month, Your mom is like I can pay 1,100 dollars a month and that used to be good enough for you, but now the landlord is like hey my bills are rising, I’m getting older, I want to make my retirement plush, I need that 2,000 I don’t need that 1,100. There’s really no bad actors in here. Just everybody trying to make this crazy economy work.