Over the holidays my dad and grandpa had a discussion about how education has shifted away from being for the pursuit of knowledge toward being only for finding a high-paying job. Now a days, there is so much stress surrounding tests, a series of numbers that determine an individual’s worth, which will lead to getting into a good college, and then a good job, and a supposedly happy life. Education doesn’t seem to be about learning anymore, but about looking good on paper. I decided to interview my grandpa on his thoughts on education, how it’s changed over his lifetime, and how textbooks have changed since he went into publishing.

Naseem Alavi: What is education?

Stuart Brewster: It’s more than learning how to read, write, and do arithmetic. It’s to become an interesting person who knows some things but is open to learning other things, and trying to find truth, whatever that is.

NA: What made you interested in education?

SB: I majored in history in college after giving up on becoming a med student. It was recommended to take courses in education to become a teacher in history, so I took education courses but I decided that wasn’t what I wanted to do. I didn’t have the resources to become a professor. When I was trying to find a job, I thought publishing might be a possibility because I’d worked in the library and I loved books. I ended up with a publishing company called Addison-Wesely that published textbooks. I didn’t set out to do it. It sort of evolved.

Stuart Brewster: It’s more than learning how to read, write, and do arithmetic. It’s to become an interesting person who knows some things but is open to learning other things, and trying to find truth, whatever that is.

NA: What made you interested in education?

SB: I majored in history in college after giving up on becoming a med student. It was recommended to take courses in education to become a teacher in history, so I took education courses but I decided that wasn’t what I wanted to do. I didn’t have the resources to become a professor. When I was trying to find a job, I thought publishing might be a possibility because I’d worked in the library and I loved books. I ended up with a publishing company called Addison-Wesely that published textbooks. I didn’t set out to do it. It sort of evolved.

NA: What was the attitude toward education when you started out?

SB: The general approach was lecture and recitation without much discussion.

NA: What were the main changes you witnessed in education through your life?

SB: The biggest change was the GI bill. Suddenly hundreds of thousands of people had an opportunity to get a college education who would’ve otherwise never been able to go. Most didn’t even have the high school background, but they could still apply, get in, and do their best. Not everyone survived to get a degree, but it changed the culture around education. Many men went to college and their wives were left to support the family, so they became teachers. Women started going to college. The expectation for them was no longer just marriage and children.

Another change is that the high school curriculum used to be very prescribed. All high schoolers in the country read the same thing. Now there’s more variety and flexibility. The AP program is an example of this. Everything used to be lecture based teaching and discussions were rare. However, there still isn’t enough support for learning. I’m worried that education won’t be at all for education but only job oriented. If you look at the biographies of the top people in their fields, I doubt you’d find that at 16 they knew what they wanted to do.

SB: The general approach was lecture and recitation without much discussion.

NA: What were the main changes you witnessed in education through your life?

SB: The biggest change was the GI bill. Suddenly hundreds of thousands of people had an opportunity to get a college education who would’ve otherwise never been able to go. Most didn’t even have the high school background, but they could still apply, get in, and do their best. Not everyone survived to get a degree, but it changed the culture around education. Many men went to college and their wives were left to support the family, so they became teachers. Women started going to college. The expectation for them was no longer just marriage and children.

Another change is that the high school curriculum used to be very prescribed. All high schoolers in the country read the same thing. Now there’s more variety and flexibility. The AP program is an example of this. Everything used to be lecture based teaching and discussions were rare. However, there still isn’t enough support for learning. I’m worried that education won’t be at all for education but only job oriented. If you look at the biographies of the top people in their fields, I doubt you’d find that at 16 they knew what they wanted to do.

NA: What was your experience with education early on in life?

SB: I never went to a public school. I went to a private elementary school and boarding preparatory school. I completed kindergarten through ninth grade at Speedwell Elementary School in Danvers, Massachusetts. There were only fifteen people in the entire school, most of which were in kindergarten and second grade. There was one room for younger kids, one room for older kids, and one room for individuals to get extra help or have discussions. One of my aunts, Marianne Bill Nickles taught in the room for older kids. At home we called her Mayam, but in school she was Ms. Nickles.

In many ways it was like homeschooling, because everyone was at a different level. We got to work at our own pace. I would be studying Algebra and the kid next to me arithmetic, and the teacher would switch between us. There were some subjects like geography that we all learned together. Discussions were rare. We did a lot of art. One year for Christmas we painted flowers on wooden bowls with oil paints. The school was on an estate, so recess meant getting to go outdoors. During the spring we could go down to the spring and catch pollywogs and keep them in the classroom until they became frogs. We learned self-discipline in that environment.

SB: I never went to a public school. I went to a private elementary school and boarding preparatory school. I completed kindergarten through ninth grade at Speedwell Elementary School in Danvers, Massachusetts. There were only fifteen people in the entire school, most of which were in kindergarten and second grade. There was one room for younger kids, one room for older kids, and one room for individuals to get extra help or have discussions. One of my aunts, Marianne Bill Nickles taught in the room for older kids. At home we called her Mayam, but in school she was Ms. Nickles.

In many ways it was like homeschooling, because everyone was at a different level. We got to work at our own pace. I would be studying Algebra and the kid next to me arithmetic, and the teacher would switch between us. There were some subjects like geography that we all learned together. Discussions were rare. We did a lot of art. One year for Christmas we painted flowers on wooden bowls with oil paints. The school was on an estate, so recess meant getting to go outdoors. During the spring we could go down to the spring and catch pollywogs and keep them in the classroom until they became frogs. We learned self-discipline in that environment.

NA: What was the attitude surrounding going to college?

SB: In my family it was a given that we’d go to college. Most, but not everyone, had gone. We were sent to preparatory boarding school that if you did well in you were more or less guaranteed entrance into college. Public schools didn’t have that. There was quite a difference between a college prep student and a general student. The general student took only the bare minimum to graduate, but that wouldn’t qualify them for college. For example, people who went to vocational school only had to take a class called General Math, which was only 7th and 8th grade math by today’s standards.

General education was much more job driven because they were expected to find a job straight out of high school. College was not. You had to take certain courses to get in, such as Latin, and once you got in there were some required courses, but those were only meant to give you a taste of different things. Sophomore year you’d decide what you wanted to specialize in. The general attitude was that majors like doctors or engineers were job driven, but others were just fields you could study with no expectation of getting a job in them. You could major in German, like my aunt Mayam, with no expectation to work with it. It was just to give you a broad background. The more things you’re exposed to, the more it gives you to draw upon in life.

Many people who became lawyers had a liberal arts background before going to law school. As time has gone on, there’s been an increasing pressure on students to have determined what their life’s work is going to be. That’s nice if you know, but there are many who don’t, and I didn’t. It turned out being a doctor just didn’t work for me. There are some people who just do well in certain subjects and not well in others, and it can be frustrating. The thing you’re really good at and are interested in might never have a job at the end, but it’s compelling to study because you enjoy it.

SB: In my family it was a given that we’d go to college. Most, but not everyone, had gone. We were sent to preparatory boarding school that if you did well in you were more or less guaranteed entrance into college. Public schools didn’t have that. There was quite a difference between a college prep student and a general student. The general student took only the bare minimum to graduate, but that wouldn’t qualify them for college. For example, people who went to vocational school only had to take a class called General Math, which was only 7th and 8th grade math by today’s standards.

General education was much more job driven because they were expected to find a job straight out of high school. College was not. You had to take certain courses to get in, such as Latin, and once you got in there were some required courses, but those were only meant to give you a taste of different things. Sophomore year you’d decide what you wanted to specialize in. The general attitude was that majors like doctors or engineers were job driven, but others were just fields you could study with no expectation of getting a job in them. You could major in German, like my aunt Mayam, with no expectation to work with it. It was just to give you a broad background. The more things you’re exposed to, the more it gives you to draw upon in life.

Many people who became lawyers had a liberal arts background before going to law school. As time has gone on, there’s been an increasing pressure on students to have determined what their life’s work is going to be. That’s nice if you know, but there are many who don’t, and I didn’t. It turned out being a doctor just didn’t work for me. There are some people who just do well in certain subjects and not well in others, and it can be frustrating. The thing you’re really good at and are interested in might never have a job at the end, but it’s compelling to study because you enjoy it.

NA: How did you experience with education affect you going into educational publishing?

SB: I’d say that publishing affected my experience with education. I got re-educated. I know more about mathematics now than from having studied it in school. I got more insight into different approaches.

NA: What was your role at Addison-Wesely?

SB: When I first applied to publishing companies, I applied for “editorial work” but I didn’t really know what that was. I never got an interview. Eventually I stumbled into Addison-Wesely and became a clerk. Addison-Wesely published high school and college level physics and math textbooks. I did internal record keeping. I became part of a sales force of people to visit colleges. It wasn’t only bringing books to people’s attention, but also finding people who were writing books. I never envisioned myself as a salesman, but teachers are salesmen. They’re exposing you to new information. It’s a challenge to go and talk to someone about how a book fits their course if you’ve never taken their class, so you ask them and then talk them into writing a book. Most people are very happy to talk about themselves.

NA: What was the most influential book you worked on?

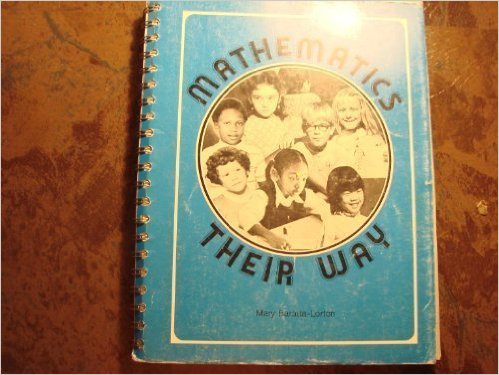

SB: Math Their Way by Mary Baratta-Lorton. It’s a K-2 activity based learning textbook written by a teacher who’d developed some pre-math and pre-language activities, and ended up tying into a whole movement that was going on at the time about experiencing learning and not just memorizing. Many argued that memorization was the only efficient way. She walked in off the street with an idea for the book and was referred to me.

SB: I’d say that publishing affected my experience with education. I got re-educated. I know more about mathematics now than from having studied it in school. I got more insight into different approaches.

NA: What was your role at Addison-Wesely?

SB: When I first applied to publishing companies, I applied for “editorial work” but I didn’t really know what that was. I never got an interview. Eventually I stumbled into Addison-Wesely and became a clerk. Addison-Wesely published high school and college level physics and math textbooks. I did internal record keeping. I became part of a sales force of people to visit colleges. It wasn’t only bringing books to people’s attention, but also finding people who were writing books. I never envisioned myself as a salesman, but teachers are salesmen. They’re exposing you to new information. It’s a challenge to go and talk to someone about how a book fits their course if you’ve never taken their class, so you ask them and then talk them into writing a book. Most people are very happy to talk about themselves.

NA: What was the most influential book you worked on?

SB: Math Their Way by Mary Baratta-Lorton. It’s a K-2 activity based learning textbook written by a teacher who’d developed some pre-math and pre-language activities, and ended up tying into a whole movement that was going on at the time about experiencing learning and not just memorizing. Many argued that memorization was the only efficient way. She walked in off the street with an idea for the book and was referred to me.

NA: What’s your opinion on common core?

SB: Basically, negative, because it’s test based. It pushes too much onto elementary school kids too early. It’s not flexible for individuals, it’s just take that test and pass it so we look good for the state evaluation. So many kids do poorly on tests, so they send them to charter or private schools, but most people can’t afford that. We need to find what’s not working. Education needs to be flexible. What works with student A won’t work with student B. It’s not a cookie cutter world.

NA: Do you think education is changing for the better?

SB: No. The current movement from public schools to charter schools is a bad idea. We need more teachers, smaller class sizes, and more human interaction between the student and teacher. The point isn’t better test scores.

NA: How can we solve the conundrum of needing tests?

SB: A good teacher knows more about a student than any test ever could. Smaller classes allow for teachers to really know the students and access them on a personal basis.

NA: What makes a good class?

SB: A good class is where the teachers and students respect each other, have individual goals, and an overall sense of unity not competition. One time I saw a man giving a math demonstration class. He kept working with one student who was having trouble to answer a problem until they got it. Meanwhile, there were all the other kids wildly raising their hands in the back of class, but he didn’t pay any attention to them.

NA: What makes a good teacher?

SB: A good teacher is passionate. Passionate for their subject, for helping students, sensitivity to students in and out of class, consistent treatment, and organization.

NA: What makes a good textbook?

SB: Much like a good teacher, it should be organized, have clarity of communication, and consistency. Math textbooks should have interesting application problems. Math is a constant battle between theory and application. You should be able to hear a voice in the textbook. When you read a novel, you can hear the writer’s style, but many textbooks are written by a committee, and any form of voice is lost.

NA: How do you hope for education to change?

SB: I hope for increasing flexibility, opportunities for teachers and students to explore, and developing the capacity to be a learner from other people. You don’t get that from sitting in front of a computer or lecturer. We need freedom of choice and opportunity. Let people try new things if they want.

SB: Basically, negative, because it’s test based. It pushes too much onto elementary school kids too early. It’s not flexible for individuals, it’s just take that test and pass it so we look good for the state evaluation. So many kids do poorly on tests, so they send them to charter or private schools, but most people can’t afford that. We need to find what’s not working. Education needs to be flexible. What works with student A won’t work with student B. It’s not a cookie cutter world.

NA: Do you think education is changing for the better?

SB: No. The current movement from public schools to charter schools is a bad idea. We need more teachers, smaller class sizes, and more human interaction between the student and teacher. The point isn’t better test scores.

NA: How can we solve the conundrum of needing tests?

SB: A good teacher knows more about a student than any test ever could. Smaller classes allow for teachers to really know the students and access them on a personal basis.

NA: What makes a good class?

SB: A good class is where the teachers and students respect each other, have individual goals, and an overall sense of unity not competition. One time I saw a man giving a math demonstration class. He kept working with one student who was having trouble to answer a problem until they got it. Meanwhile, there were all the other kids wildly raising their hands in the back of class, but he didn’t pay any attention to them.

NA: What makes a good teacher?

SB: A good teacher is passionate. Passionate for their subject, for helping students, sensitivity to students in and out of class, consistent treatment, and organization.

NA: What makes a good textbook?

SB: Much like a good teacher, it should be organized, have clarity of communication, and consistency. Math textbooks should have interesting application problems. Math is a constant battle between theory and application. You should be able to hear a voice in the textbook. When you read a novel, you can hear the writer’s style, but many textbooks are written by a committee, and any form of voice is lost.

NA: How do you hope for education to change?

SB: I hope for increasing flexibility, opportunities for teachers and students to explore, and developing the capacity to be a learner from other people. You don’t get that from sitting in front of a computer or lecturer. We need freedom of choice and opportunity. Let people try new things if they want.