"Today, fanfiction is a staple of fandom. Despite, or perhaps because of this, it remains a topic of scrutiny by the public and by many authors." — Zoe Jung, 10th Grade

Quarantine sent people scrambling for new hobbies and coping mechanisms. One of these was fanfiction. Fanfiction visibility has gone up in recent years, and people’s engagement with it skyrocketed over quarantine. This means more opinions are popping up trying to categorize it. Both original writers and some opinionated non-writers assert that fanfiction does not belong in the literary sphere, neither of them acknowledging their own ulterior motivations.

Fanfiction is fiction based on an original work, written by someone other than the creator of the work. It’s also commonly referred to as transformative fiction, fanworks, or transformative works. The actual definition of fanfiction has been debated, with at least one survey conducted to try to determine a common definition.

The modern conception of fanfiction began within the last hundred years. In her thesis Revision as Resistance: Fanfiction as an Empowering Community for Female and Queer Fans at the University of Connecticut, Diana Koehm writes that “fanfiction as we know it today originated in the late 1960s as a response to the TV show [Star Trek] (1966-69).” The series was originally set to be canceled after its second season in 1968. Star Trek fans Bjo and John Trimble started a grassroots letter-writing campaign called “Save Star Trek,” which continued until the network said that Star Trek would not be canceled and to please stop writing letters.

“Save Star Trek” is thought to be the first undeniably successful fan campaign to save a TV show. This success is what first showed the Star Trek fandom to be more than the fan communities who came before it. Star Trek’s third season allowed it to enter syndication, so it could be rerun on different networks and eventually become the phenomenon that it is today.

Importantly, the consolidation of the Star Trek fandom led to a lot of scorn from older, white male science fiction fans. It’s important to keep in mind that science fiction fandom has historically been composed of a majority of white men, who now felt their reputation was being threatened by this new community of women. Star Trek was a leader in casting diversity at the time, and the fandom that gathered around it was often young and mostly women. Many literary sci-fi fans were upset at the influx of Trek fans into sci-fi spaces. The term “media fandom” was created to describe Star Trek fans, meaning fans who engaged mainly with TV and movie sci-fi rather than book sci-fi, and specifically those who wrote fanfiction. The term “Trekkies” was also created as a derogatory name for female Star Trek fans, stereotyped as shallow and uninterested in nuanced enjoyment of sci-fi. Thus, modern fanfiction has been criticized from the very beginning.

“Media fandom” is thought by some to have diverged from sci-fi fandom to become modern fandom, which is still largely female, and where literary and visual media fandoms are no longer separate. This scorn and separation was, one could argue, the beginning of the same fandom gatekeeping we see today.

There’s long been an argument over whether or not fanfiction is “real writing.” Though it started with the straight male sci-fi nerds of the 60’s, this gatekeeping is no longer confined to that demographic. R.S. Benedict, a relatively obscure author, wrote a long thread on January 14–16, 2021, where she condemned fanfiction as “low-effort,” “formulaic,” and “lowest-common-denominator” writing. The most notable piece in regards to this article is the sixth tweet: “IMO arguing that women need fanfiction is profoundly misogynistic. I'm a woman, and I can read and write actual stories. I don't need training wheels.”

By saying this, Benedict implies that fanfiction is not “actual stories.” Presumably, she defines actuality by originality. A quick Google search will bring up dozens of articles defending fanfiction as real writing, but the problem is in the question: what is real writing?

However well hidden it may be, the idea that some writing is "real" and some is not is inherently gatekeeping. Even if fanfiction is argued definitively into the “real writing” box, the cooperation with the terms of the argument indirectly validates the argument’s basis: that “real writing” is a definitive category that exists, and that some writing does not fall into it. So really, the only way to beat the argument is to not engage with it on its own terms.

The problem is that these categories of valid and invalid writing don’t actually exist. What people really mean when they say fanfiction isn’t real writing is that it’s bad writing. Benedict helpfully displays this phenomenon: her first Tweet calls fanfiction “a form that actively teaches you to write worse.” Some of what she’s mentioned—fanfiction being formulaic, tropey, low-effort—are reasons used in both arguments. This isn’t untrue for a significant amount of fanfiction. Of course it isn’t. There are no quality controls for fanfiction: it’s published online and the majority of it isn’t edited. As with any kind of art, bad quality abounds. But many people seem to want to judge all fanfiction on the merit of a fraction of the works.

The derivativeness of fanfiction is unsurprisingly the main way people discredit it. This includes arguments like: writers need to learn to develop their own characters; writers are wasting their creative juices on someone else’s intellectual property; and worldbuilding (as in, creating a world) is a necessary part of writing. The glaring flaw here, which is often pointed out in arguments defending fanfiction, is that most or all writing contains some degree of borrowing. Canonical works are often used as examples of this: John Milton’s Paradise Lost used characters from the Bible while T. H. White’s The Once and Future King was based on Arthurian legend and Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. Writers don’t exist in a void, and there are only so many ideas out there. The important part of writing isn’t to make up a premise or even make up a character; it’s what you do with it, and the perspective you bring into your writing, that make it your own.

The final reason why authors disparage fanfiction is their possessiveness over their work. This is a reasonable feeling: writers put pieces of themselves into their writing. But this possessiveness is sometimes taken to extremes—like how Diana Galbadon, author of the Outlander series, compares writing fanfiction of her characters to sex-trafficking her children. It’s understandable not to want other people messing around in the universe you created, constructing bad plots, getting the characters wrong, or writing them into “simple-minded sex fantasies,” as Galbadon says. The problem is when writers act on these feelings by trying to invalidate an entire genre of writing. When they pretend their motivations are less personal, it just makes the problem worse.

Consider also that once something is published, it’s effectively public property. All writers have to relinquish control of their work once it’s published, because they can’t control how the public interacts with it after that. Some control remains in the form of copyright laws, but as fanfiction is generally non-monetized and transformative, it is usually judged as fair use and therefore legal. Writers don’t have the ability to choose how people engage with their published works, though some struggle to accept that.

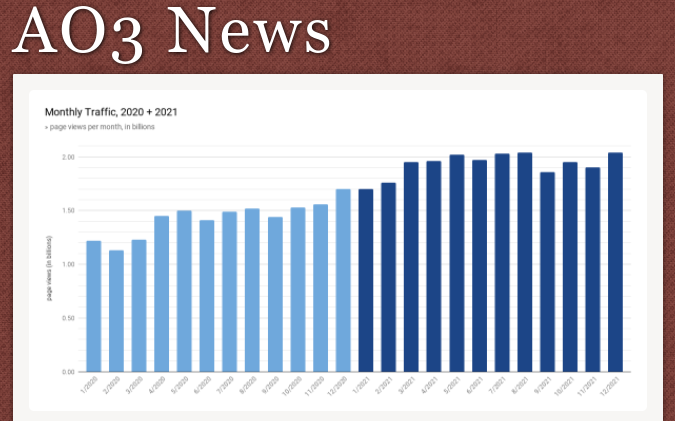

Today, fanfiction is a staple of fandom. Sites like FanFiction.Net (FFN or FF.net) and Archive of Our Own (AO3) host millions of individual works of fanfiction. Despite, or perhaps because of this, it remains a topic of scrutiny by the public and by many authors. Media fandom (used to describe fan communities with a focus on making creative works around their media) is stereotyped in many derogatory ways. The popular image of fans tends to be the fangirl: a teenager, writing bad fanfiction and squealing over Twilight or One Direction. This image, and the derision implicit in imagining it, are manifestations of the deep-seated misogyny that has followed media fandom wherever it lands.

Take sports fandoms. It’s been argued that these highly-male gatherings are a method of finding the emotional communication that is largely denied to men by the patriarchy’s view of emotions as weak. Sports fandoms are largely curative rather than transformative, meaning they have a focus on analysis rather than creation. (This does not include fantasy sports leagues, which are somewhere between curative and transformative because they use existing players and their stats to form new teams.) They are also accepted and normalized throughout Western society in a way that no other kind of fandom is. But while sports fandom may be used to reach hidden emotional connection, general fandom is looked down on for its emphasis on feelings.

One article in the Transformative Works and Cultures journal calls fandom an “affective hermeneutic,” or way of gaining knowledge through feeling. Women in fandom are exaggerated as hysterics, or fanatics, or freaks—as fanfiction is often thought of as pornography, or inherently erotic, by misinformed outsiders. As Koehm writes, fandom is often a space for women, especially queer women, to connect and to transform media into something for each other rather than for the straight, cis male target audience. That scares them, and they often channel their fear into scorn and disgust.

The gatekeeping of fanfiction in literary spaces may be less about fanfiction itself, and more a manifestation of a larger societal problem. The things women enjoy and do are not considered legitimate until they are done by men, who then exclude women from participating. Benedict is inside the ivory tower of publishing. In addition to saying that “arguing that women need fanfiction is profoundly misogynistic,” she also argues that “the popularity of fanfic has served to erase meaningful queer literature.” In saying this, she misconstrues the relationship with and need for fanfiction in both of these communities. Queer women need fanfiction not in addition to traditional publication, but in its absence. Benedict has forgotten that she is not the norm. The same openness that allows so much bad fanfiction also makes it far more accessible than traditional publication. The derisive view of fanfiction is rooted in misogyny, and media fandom is just one of many activities that have been devalued by society because they are done mostly by women. It’s a way for queer women to reclaim the space that has been denied to them.

Works Cited:

Cavna, Michael

“How Star Trek embraced diversity 50 years ago — and continues to do so today”

The Washington Post

July 20, 2016

Koehm, Diana

"Revision as Resistance: Fanfiction as an Empowering Community for Female and Queer Fans"

Honors Scholar Theses. 604.

Dec. 28, 2018

https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/604.

Wilson, Anna

"The Role of Affect in Fan Fiction."

In "The Classical Canon and/as Transformative Work," edited by Ika Willis, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 21.

Mar. 3, 2016

https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2016.0684.

Yatrakis, Christina,

"Fan fiction, fandoms, and literature: or, why it’s time to pay attention to fan fiction"

2013

College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 145. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/145.

Fanfiction is fiction based on an original work, written by someone other than the creator of the work. It’s also commonly referred to as transformative fiction, fanworks, or transformative works. The actual definition of fanfiction has been debated, with at least one survey conducted to try to determine a common definition.

The modern conception of fanfiction began within the last hundred years. In her thesis Revision as Resistance: Fanfiction as an Empowering Community for Female and Queer Fans at the University of Connecticut, Diana Koehm writes that “fanfiction as we know it today originated in the late 1960s as a response to the TV show [Star Trek] (1966-69).” The series was originally set to be canceled after its second season in 1968. Star Trek fans Bjo and John Trimble started a grassroots letter-writing campaign called “Save Star Trek,” which continued until the network said that Star Trek would not be canceled and to please stop writing letters.

“Save Star Trek” is thought to be the first undeniably successful fan campaign to save a TV show. This success is what first showed the Star Trek fandom to be more than the fan communities who came before it. Star Trek’s third season allowed it to enter syndication, so it could be rerun on different networks and eventually become the phenomenon that it is today.

Importantly, the consolidation of the Star Trek fandom led to a lot of scorn from older, white male science fiction fans. It’s important to keep in mind that science fiction fandom has historically been composed of a majority of white men, who now felt their reputation was being threatened by this new community of women. Star Trek was a leader in casting diversity at the time, and the fandom that gathered around it was often young and mostly women. Many literary sci-fi fans were upset at the influx of Trek fans into sci-fi spaces. The term “media fandom” was created to describe Star Trek fans, meaning fans who engaged mainly with TV and movie sci-fi rather than book sci-fi, and specifically those who wrote fanfiction. The term “Trekkies” was also created as a derogatory name for female Star Trek fans, stereotyped as shallow and uninterested in nuanced enjoyment of sci-fi. Thus, modern fanfiction has been criticized from the very beginning.

“Media fandom” is thought by some to have diverged from sci-fi fandom to become modern fandom, which is still largely female, and where literary and visual media fandoms are no longer separate. This scorn and separation was, one could argue, the beginning of the same fandom gatekeeping we see today.

There’s long been an argument over whether or not fanfiction is “real writing.” Though it started with the straight male sci-fi nerds of the 60’s, this gatekeeping is no longer confined to that demographic. R.S. Benedict, a relatively obscure author, wrote a long thread on January 14–16, 2021, where she condemned fanfiction as “low-effort,” “formulaic,” and “lowest-common-denominator” writing. The most notable piece in regards to this article is the sixth tweet: “IMO arguing that women need fanfiction is profoundly misogynistic. I'm a woman, and I can read and write actual stories. I don't need training wheels.”

By saying this, Benedict implies that fanfiction is not “actual stories.” Presumably, she defines actuality by originality. A quick Google search will bring up dozens of articles defending fanfiction as real writing, but the problem is in the question: what is real writing?

However well hidden it may be, the idea that some writing is "real" and some is not is inherently gatekeeping. Even if fanfiction is argued definitively into the “real writing” box, the cooperation with the terms of the argument indirectly validates the argument’s basis: that “real writing” is a definitive category that exists, and that some writing does not fall into it. So really, the only way to beat the argument is to not engage with it on its own terms.

The problem is that these categories of valid and invalid writing don’t actually exist. What people really mean when they say fanfiction isn’t real writing is that it’s bad writing. Benedict helpfully displays this phenomenon: her first Tweet calls fanfiction “a form that actively teaches you to write worse.” Some of what she’s mentioned—fanfiction being formulaic, tropey, low-effort—are reasons used in both arguments. This isn’t untrue for a significant amount of fanfiction. Of course it isn’t. There are no quality controls for fanfiction: it’s published online and the majority of it isn’t edited. As with any kind of art, bad quality abounds. But many people seem to want to judge all fanfiction on the merit of a fraction of the works.

The derivativeness of fanfiction is unsurprisingly the main way people discredit it. This includes arguments like: writers need to learn to develop their own characters; writers are wasting their creative juices on someone else’s intellectual property; and worldbuilding (as in, creating a world) is a necessary part of writing. The glaring flaw here, which is often pointed out in arguments defending fanfiction, is that most or all writing contains some degree of borrowing. Canonical works are often used as examples of this: John Milton’s Paradise Lost used characters from the Bible while T. H. White’s The Once and Future King was based on Arthurian legend and Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. Writers don’t exist in a void, and there are only so many ideas out there. The important part of writing isn’t to make up a premise or even make up a character; it’s what you do with it, and the perspective you bring into your writing, that make it your own.

The final reason why authors disparage fanfiction is their possessiveness over their work. This is a reasonable feeling: writers put pieces of themselves into their writing. But this possessiveness is sometimes taken to extremes—like how Diana Galbadon, author of the Outlander series, compares writing fanfiction of her characters to sex-trafficking her children. It’s understandable not to want other people messing around in the universe you created, constructing bad plots, getting the characters wrong, or writing them into “simple-minded sex fantasies,” as Galbadon says. The problem is when writers act on these feelings by trying to invalidate an entire genre of writing. When they pretend their motivations are less personal, it just makes the problem worse.

Consider also that once something is published, it’s effectively public property. All writers have to relinquish control of their work once it’s published, because they can’t control how the public interacts with it after that. Some control remains in the form of copyright laws, but as fanfiction is generally non-monetized and transformative, it is usually judged as fair use and therefore legal. Writers don’t have the ability to choose how people engage with their published works, though some struggle to accept that.

Today, fanfiction is a staple of fandom. Sites like FanFiction.Net (FFN or FF.net) and Archive of Our Own (AO3) host millions of individual works of fanfiction. Despite, or perhaps because of this, it remains a topic of scrutiny by the public and by many authors. Media fandom (used to describe fan communities with a focus on making creative works around their media) is stereotyped in many derogatory ways. The popular image of fans tends to be the fangirl: a teenager, writing bad fanfiction and squealing over Twilight or One Direction. This image, and the derision implicit in imagining it, are manifestations of the deep-seated misogyny that has followed media fandom wherever it lands.

Take sports fandoms. It’s been argued that these highly-male gatherings are a method of finding the emotional communication that is largely denied to men by the patriarchy’s view of emotions as weak. Sports fandoms are largely curative rather than transformative, meaning they have a focus on analysis rather than creation. (This does not include fantasy sports leagues, which are somewhere between curative and transformative because they use existing players and their stats to form new teams.) They are also accepted and normalized throughout Western society in a way that no other kind of fandom is. But while sports fandom may be used to reach hidden emotional connection, general fandom is looked down on for its emphasis on feelings.

One article in the Transformative Works and Cultures journal calls fandom an “affective hermeneutic,” or way of gaining knowledge through feeling. Women in fandom are exaggerated as hysterics, or fanatics, or freaks—as fanfiction is often thought of as pornography, or inherently erotic, by misinformed outsiders. As Koehm writes, fandom is often a space for women, especially queer women, to connect and to transform media into something for each other rather than for the straight, cis male target audience. That scares them, and they often channel their fear into scorn and disgust.

The gatekeeping of fanfiction in literary spaces may be less about fanfiction itself, and more a manifestation of a larger societal problem. The things women enjoy and do are not considered legitimate until they are done by men, who then exclude women from participating. Benedict is inside the ivory tower of publishing. In addition to saying that “arguing that women need fanfiction is profoundly misogynistic,” she also argues that “the popularity of fanfic has served to erase meaningful queer literature.” In saying this, she misconstrues the relationship with and need for fanfiction in both of these communities. Queer women need fanfiction not in addition to traditional publication, but in its absence. Benedict has forgotten that she is not the norm. The same openness that allows so much bad fanfiction also makes it far more accessible than traditional publication. The derisive view of fanfiction is rooted in misogyny, and media fandom is just one of many activities that have been devalued by society because they are done mostly by women. It’s a way for queer women to reclaim the space that has been denied to them.

Works Cited:

Cavna, Michael

“How Star Trek embraced diversity 50 years ago — and continues to do so today”

The Washington Post

July 20, 2016

Koehm, Diana

"Revision as Resistance: Fanfiction as an Empowering Community for Female and Queer Fans"

Honors Scholar Theses. 604.

Dec. 28, 2018

https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/604.

Wilson, Anna

"The Role of Affect in Fan Fiction."

In "The Classical Canon and/as Transformative Work," edited by Ika Willis, special issue, Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 21.

Mar. 3, 2016

https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2016.0684.

Yatrakis, Christina,

"Fan fiction, fandoms, and literature: or, why it’s time to pay attention to fan fiction"

2013

College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 145. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/145.