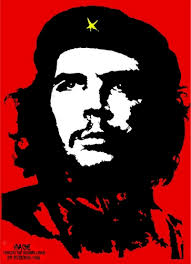

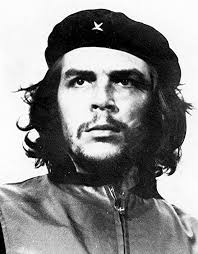

Who is the man with the gold star in the center of his black beret? His face reduced to the black and white image of wild hair, eyes turned to the horizon. Che Guevara, made iconic in the United States not only for his rebellion, but for the way in which the media reacted:by making him a marketable mascot. Che Guevara was a South American doctor turned Marxist revolutionary. Guevara played significant roles in the Cuban revolution, (an armed rebellion led by Fidel Castro in 1958 against dictator Fulgencio Batista) and held important political positions in Fidel Castro’s regime.

It is not uncommon to see people in the Bay Area (particularly young people) wearing Che Guevara t-shirts or pins, advertising the man they believe to be a symbol of revolution and hero for the underdog. But if there is so much more to Guevara than this, why does the majority know so little?

We know so little because we receive only enough to still want to buy the icon we have been given. The process of consuming half or one side of a story as whole is a form of consumerism. What will America consume? What can be simplified for the middle class, what will make the most money, and how do we get there?

A political figure comes onto the playing field, the media latches on, repackages the figure into a simplified icon, consumers receive. But the figure we are given is not necessarily the whole story, and more often than not they have been warped and simplified to make their beliefs easily digestible. They have either been (in the case of Che Guevara) simplified for uncontroversial consumption, or simplified into the clear-cut caricatures of violence that we, as consumers of media, can generally hate without moral struggle. The image of Che represents the former, a man dedicated to the freedom of his country, with no violent intent.

It is not uncommon to see people in the Bay Area (particularly young people) wearing Che Guevara t-shirts or pins, advertising the man they believe to be a symbol of revolution and hero for the underdog. But if there is so much more to Guevara than this, why does the majority know so little?

We know so little because we receive only enough to still want to buy the icon we have been given. The process of consuming half or one side of a story as whole is a form of consumerism. What will America consume? What can be simplified for the middle class, what will make the most money, and how do we get there?

A political figure comes onto the playing field, the media latches on, repackages the figure into a simplified icon, consumers receive. But the figure we are given is not necessarily the whole story, and more often than not they have been warped and simplified to make their beliefs easily digestible. They have either been (in the case of Che Guevara) simplified for uncontroversial consumption, or simplified into the clear-cut caricatures of violence that we, as consumers of media, can generally hate without moral struggle. The image of Che represents the former, a man dedicated to the freedom of his country, with no violent intent.

For the American people, Che is the underdog’s fight for freedom under a sadistic, evil rule. As Americans, the institutionalized patriotism we have inherited from our schooling and structures allows us to sympathise: we want him to win. But people often don’t learn about the thoughtless acts of violence Che committed; this history can be found, but it must be sought out, we are only given what we know we can easily understand.

On the other side of the spectrum, one of the ways in which the media has reduced political figures to a profile of violence can be seen in the Black Panther Party, a social activist group based in Oakland California in the ‘60s. Originating as a group dedicated to defending black people from police brutality, the Black Panthers grew to represent the black struggle for equal rights, representation, and justice in the United States.

This powerful, complex party was simplified by the media to one quality: violence. They believed black people had the right to bear arms (citing the Constitution), stating that black people were not safe and deserved a right to defend themselves. Instead, the media reduced them to what white, ‘60s, America, could understand and consume. The media drained The Black Panthers of all complexity and positive intent, labeling them as another black group that condoned violence. This raises the question, how and why does the media simplify and repackage a political figure for our consumption?

When the media simplifies something, we do one of two things. Either we mythologize it, creating a narrative that we feel comfortable with, as is the case with Che Guevara--or dismiss it entirely, as with the Black Panthers,because society does not know how to reconcile with a complex morality. In turning Che Guevara into a t-shirt icon, he was made safe because we are taught to believe in the narrative that harmful people are not placed on t-shirts. To put someone on a t-shirt is to turn a political figure into an icon for the purpose of merchandising it; a form of mythologisation.

The process of simplifying people and groups into icons and representations of what we are already comfortable with is not new. It is a part of the human process of reinforcing our own beliefs, it is just another way to surround ourselves with what we know and remove moral struggle from our lives. What is being repackaged for our consumption is acts of rebellion to conform to a narrative that we live in; the narrative that revolution itself is a myth.

On the other side of the spectrum, one of the ways in which the media has reduced political figures to a profile of violence can be seen in the Black Panther Party, a social activist group based in Oakland California in the ‘60s. Originating as a group dedicated to defending black people from police brutality, the Black Panthers grew to represent the black struggle for equal rights, representation, and justice in the United States.

This powerful, complex party was simplified by the media to one quality: violence. They believed black people had the right to bear arms (citing the Constitution), stating that black people were not safe and deserved a right to defend themselves. Instead, the media reduced them to what white, ‘60s, America, could understand and consume. The media drained The Black Panthers of all complexity and positive intent, labeling them as another black group that condoned violence. This raises the question, how and why does the media simplify and repackage a political figure for our consumption?

When the media simplifies something, we do one of two things. Either we mythologize it, creating a narrative that we feel comfortable with, as is the case with Che Guevara--or dismiss it entirely, as with the Black Panthers,because society does not know how to reconcile with a complex morality. In turning Che Guevara into a t-shirt icon, he was made safe because we are taught to believe in the narrative that harmful people are not placed on t-shirts. To put someone on a t-shirt is to turn a political figure into an icon for the purpose of merchandising it; a form of mythologisation.

The process of simplifying people and groups into icons and representations of what we are already comfortable with is not new. It is a part of the human process of reinforcing our own beliefs, it is just another way to surround ourselves with what we know and remove moral struggle from our lives. What is being repackaged for our consumption is acts of rebellion to conform to a narrative that we live in; the narrative that revolution itself is a myth.