"America’s culture around the rampant state of depression and our tendency to rush into miracle treatments creates somewhat of a perfect storm. This, if handled poorly, could continue to feed into our country’s already out-of-control opiate crisis." -- Miles De Rosa

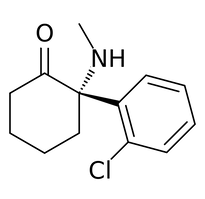

On March Fourth of 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new “miracle” anti-depressant nasal spray called esketamine. The drug, to be marketed under the name Spravato, is a derivative of the common party drug Ketamine. Compounds akin to Ketamine have been administered in clinics throughout the country, starting in the mid-nineties, as a solution for people whose depression has proven to be resistant to more traditional treatments. The results are extremely polarizing.

Ketamine got its start in 1970 as an intravenous (IV) anesthetic. It has since been used both as an anesthetic for short procedures, and as a short-term pain killer. It found its way out of clinical settings and into the hands of abusers in the mid-nineties as a hallucinogenic party drug (right). Even when administered clinically it cause hallucinations, and dissociative, psychedelic effects.

Ketamine got its start in 1970 as an intravenous (IV) anesthetic. It has since been used both as an anesthetic for short procedures, and as a short-term pain killer. It found its way out of clinical settings and into the hands of abusers in the mid-nineties as a hallucinogenic party drug (right). Even when administered clinically it cause hallucinations, and dissociative, psychedelic effects.

Ketamine is already a fairly common treatment for severe depression. Many psych wards and hospitals offer it as a treatment for those who have failed to find success elsewhere. Some hospitals and wards have found a great deal of success, with one clinic in Texas boasting a 91% success rate in treating depression with the drug. Most clinics post rates of success around 80%.

Others, though, are not convinced. William V. Bobo, a psychiatrist who focuses on treating depression at Minnesota’s Mayo Clinic, says that "We know that we can infuse ketamine acutely and have a certain rate of success. But even when we give multiple infusions over, say, a two-week period, a lot of patients will relapse in about 18 days.” Those results are not entirely encouraging.

Esketamine was also fast-tracked by the FDA, despite only one of the three clinical trials yielding successful results; most drugs have to go through at least two to be approved by the FDA. Depression in an epidemic in the United States, and any new potential treatment is often welcomed, which may explain why the drug was pushed through the process.

All three clinical trials were administered by Janssen, the pharmaceutical company developing the drug. Janssen is projected to carve out a $12 billion chunk in the antidepressant market when esketamine hits shelves.

This FDA approval though, came with some strings attached. The treatment is supposed to be administered twice a week for four weeks, with boosters as needed, while also giving the patient a traditional daily antidepressant. The FDA mandated that these treatments be administered in a clinical setting, with a physician present.

Though this model has been successful in the past, we don’t know how or why. Studies have shown that Ketamine works to relieve severe depression, at least in the short term and often in the long term, but what they haven’t shown is entirely how. One study, conducted at Stanford by Dr. Nolan Williams and Dr. Boris Heifets, revealed that much of the antidepressant effect appears to be a result of its interaction with the opiate receptors in the brain.

In the study they gave Ketamine to 30 patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression. Beforehand, some were given a placebo, and some were given Naltrexone, an opiate inhibitor that blocks the receptors. The study revealed that taking this inhibitor nearly or completely eliminated the antidepressant effects of the drug. Unfortunately, the study was cut short due to patient well-being. The study concluded that because the drug works by occupying opiate receptors to combat depression, it may contribute to opioid dependence for those at risk, or a ketamine addiction.

Most media sources reporting on this new drug, such as the The New York Times, have echoed Janssen’s position that we don’t know how this drug works. Which raises the question, is Janssen aware of why it’s drug works and just hiding it from the FDA for the sake of approval, or are they truly in the dark about it’s effectiveness, as they claim to be.

On the surface, this looks an awful lot like the beginning of the opiate crisis. In the early nineties, Pharmaceutical companies engineered and pushed a supposed miracle drug to treat a previously untreatable chronic condition (with the opiate crisis it was chronic pain, for esketamine it’s treatment resistant depression), the industry gets excited, eventually moving forward with the treatment without fully understanding the potential long-term impacts, and it ends with thousands of deaths, and thousands more addictions.

But the FDA is taking additional precautions this time around the block. First of all, the treatment would only be administered twice a week, for four weeks, with boosters as necessary. This is also in conjunction with a traditional antidepressant. The goal of esketamine is to get people whose depression is considered treatment resistant to a point to where they can live fulfilling lives with just a standard SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) antidepressant - such as Prozac (right) or Lexapro. All of these treatments are to be administered by and under the supervision of physicians.

Before Ketamine became an FDA-approved option, infusions used to cost $500 per treatment, or $4,000 dollars for four weeks, twice a week. Because it was not FDA approved, this was usually paid by patients out-of-pocket. The price of esketamine treatments are said to be between $4,720 - $6,785 for the entire four week treatment. But because the new drug esketamine is FDA-approved, it will be covered by insurance— and most likely accompanied by a sizeable copay.

This still poses issues when it comes to people becoming addicted. Ketamine on the street reportedly goes for about $30 for a gram. If a patient were to try the ketamine treatment, feel better, and then go off of it, only to return to a state of major depression, they may not be able to get another round of treatment covered by insurance. In this case, it would be a lot cheaper and more potent to just buy the drug on the street, a similar story to the one we saw playout during the opiate crisis over and over again. Those who are unable to get the only treatment that worked for them, will turn to the more powerful, more abundant, and cheaper street equivalent.

America’s culture around the rampant state of depression and our tendency to rush into miracle treatments creates somewhat of a perfect storm. This, if handled poorly, could continue to feed into our country’s already out-of-control opiate crisis. Fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice…

Others, though, are not convinced. William V. Bobo, a psychiatrist who focuses on treating depression at Minnesota’s Mayo Clinic, says that "We know that we can infuse ketamine acutely and have a certain rate of success. But even when we give multiple infusions over, say, a two-week period, a lot of patients will relapse in about 18 days.” Those results are not entirely encouraging.

Esketamine was also fast-tracked by the FDA, despite only one of the three clinical trials yielding successful results; most drugs have to go through at least two to be approved by the FDA. Depression in an epidemic in the United States, and any new potential treatment is often welcomed, which may explain why the drug was pushed through the process.

All three clinical trials were administered by Janssen, the pharmaceutical company developing the drug. Janssen is projected to carve out a $12 billion chunk in the antidepressant market when esketamine hits shelves.

This FDA approval though, came with some strings attached. The treatment is supposed to be administered twice a week for four weeks, with boosters as needed, while also giving the patient a traditional daily antidepressant. The FDA mandated that these treatments be administered in a clinical setting, with a physician present.

Though this model has been successful in the past, we don’t know how or why. Studies have shown that Ketamine works to relieve severe depression, at least in the short term and often in the long term, but what they haven’t shown is entirely how. One study, conducted at Stanford by Dr. Nolan Williams and Dr. Boris Heifets, revealed that much of the antidepressant effect appears to be a result of its interaction with the opiate receptors in the brain.

In the study they gave Ketamine to 30 patients suffering from treatment-resistant depression. Beforehand, some were given a placebo, and some were given Naltrexone, an opiate inhibitor that blocks the receptors. The study revealed that taking this inhibitor nearly or completely eliminated the antidepressant effects of the drug. Unfortunately, the study was cut short due to patient well-being. The study concluded that because the drug works by occupying opiate receptors to combat depression, it may contribute to opioid dependence for those at risk, or a ketamine addiction.

Most media sources reporting on this new drug, such as the The New York Times, have echoed Janssen’s position that we don’t know how this drug works. Which raises the question, is Janssen aware of why it’s drug works and just hiding it from the FDA for the sake of approval, or are they truly in the dark about it’s effectiveness, as they claim to be.

On the surface, this looks an awful lot like the beginning of the opiate crisis. In the early nineties, Pharmaceutical companies engineered and pushed a supposed miracle drug to treat a previously untreatable chronic condition (with the opiate crisis it was chronic pain, for esketamine it’s treatment resistant depression), the industry gets excited, eventually moving forward with the treatment without fully understanding the potential long-term impacts, and it ends with thousands of deaths, and thousands more addictions.

But the FDA is taking additional precautions this time around the block. First of all, the treatment would only be administered twice a week, for four weeks, with boosters as necessary. This is also in conjunction with a traditional antidepressant. The goal of esketamine is to get people whose depression is considered treatment resistant to a point to where they can live fulfilling lives with just a standard SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) antidepressant - such as Prozac (right) or Lexapro. All of these treatments are to be administered by and under the supervision of physicians.

Before Ketamine became an FDA-approved option, infusions used to cost $500 per treatment, or $4,000 dollars for four weeks, twice a week. Because it was not FDA approved, this was usually paid by patients out-of-pocket. The price of esketamine treatments are said to be between $4,720 - $6,785 for the entire four week treatment. But because the new drug esketamine is FDA-approved, it will be covered by insurance— and most likely accompanied by a sizeable copay.

This still poses issues when it comes to people becoming addicted. Ketamine on the street reportedly goes for about $30 for a gram. If a patient were to try the ketamine treatment, feel better, and then go off of it, only to return to a state of major depression, they may not be able to get another round of treatment covered by insurance. In this case, it would be a lot cheaper and more potent to just buy the drug on the street, a similar story to the one we saw playout during the opiate crisis over and over again. Those who are unable to get the only treatment that worked for them, will turn to the more powerful, more abundant, and cheaper street equivalent.

America’s culture around the rampant state of depression and our tendency to rush into miracle treatments creates somewhat of a perfect storm. This, if handled poorly, could continue to feed into our country’s already out-of-control opiate crisis. Fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice…