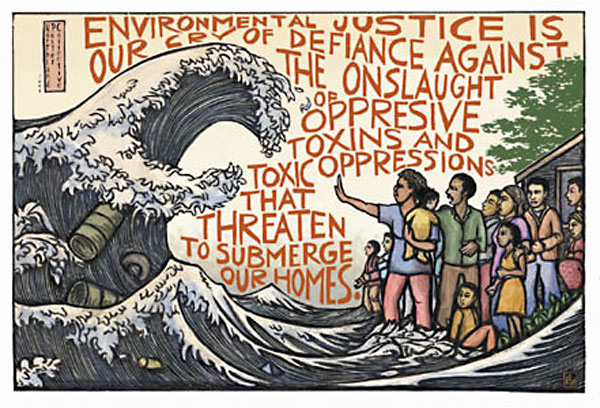

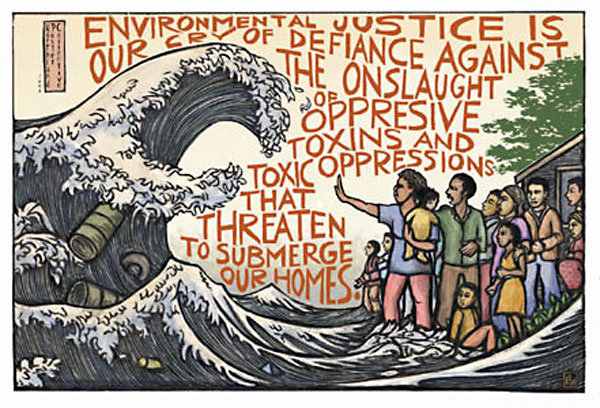

With President Donald Trump’s denial of climate change, there is also an inherent denial of people of color’s experiences in circumstances where they are most targeted by the world’s environmental realities. When a group is marginalized, it shows up everywhere. In spaces such as health care, the legal system, and the environment, the marginalization of groups such as people of color become present. In the discussion of climate change and the state of crisis that the globe finds itself in, there is a lack of conversation about how intersectionality shows up in environmental politics. However, when we pay attention to situations such as the recent hurricane disasters, it is overwhelmingly clear that people of color receive the deadliest end of climate change.

In recent years, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has championed environmental and climate justice: a movement that seeks to include race and socioeconomic status as a core part of the discussion of our climate. They describe environmental injustice and climate change as “about the fact that in many communities it is far easier to find a bag of Cheetos than a carton of strawberries and this only stands to get worse as drought and flooding impact the availability and affordability of nutritious food.” Among other disparities and injustices, people of color deserve to be in the spotlight of advocacy for the environment.

Robert Bullard, professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, says “oftentimes, low-income communities and communities of color don’t get the necessary protection when it comes to flood control” which means that in areas where people of color are the majority, the government often doesn’t put in embankments to keep flood water at bay. Where as in similar situations with more privileged communities, they do. Records of government funding for protection against and recovery from natural disasters show instances in which the government has not invested as much in low income communities.

After Hurricane Katrina, black homeowners received $8,000 less in government aid than white homeowners due to the so-called “difference in housing values.” In 2013, about 80 percent of the primarily black residents of the New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward had not returned to their community because of the inadequate building efforts and lack of funds to recover homes. Charon Dawson, a member of the Oakland Urban Search & Rescue team, explains that in the aftermath of hurricanes there were “buildings completely flat, buildings turn[ed] on their side, cars in neighborhoods, because of the surge of the storm.” Reconstruction after natural disasters is not a simple task and without the income to do so is nearly impossible. The funds to rebuild decrease even more because many of the people in these communities can’t afford flood insurance.

In recent years, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has championed environmental and climate justice: a movement that seeks to include race and socioeconomic status as a core part of the discussion of our climate. They describe environmental injustice and climate change as “about the fact that in many communities it is far easier to find a bag of Cheetos than a carton of strawberries and this only stands to get worse as drought and flooding impact the availability and affordability of nutritious food.” Among other disparities and injustices, people of color deserve to be in the spotlight of advocacy for the environment.

Robert Bullard, professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, says “oftentimes, low-income communities and communities of color don’t get the necessary protection when it comes to flood control” which means that in areas where people of color are the majority, the government often doesn’t put in embankments to keep flood water at bay. Where as in similar situations with more privileged communities, they do. Records of government funding for protection against and recovery from natural disasters show instances in which the government has not invested as much in low income communities.

After Hurricane Katrina, black homeowners received $8,000 less in government aid than white homeowners due to the so-called “difference in housing values.” In 2013, about 80 percent of the primarily black residents of the New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward had not returned to their community because of the inadequate building efforts and lack of funds to recover homes. Charon Dawson, a member of the Oakland Urban Search & Rescue team, explains that in the aftermath of hurricanes there were “buildings completely flat, buildings turn[ed] on their side, cars in neighborhoods, because of the surge of the storm.” Reconstruction after natural disasters is not a simple task and without the income to do so is nearly impossible. The funds to rebuild decrease even more because many of the people in these communities can’t afford flood insurance.

It isn’t just natural disasters that are disproportionately affecting people of color and low-income people in our communities. Industrialization and factories, mining, and chemicals are also affecting people of color at a higher frequency and degree. Sixty-eight percent of African-American people in the U.S. live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant, which has endless negative effects that can severely damage a person’s health.

One of the most public representations of environmental injustice was the Flint, Michigan water crisis. Michigan Representative Dan Kildee says that he “just [doesn’t] believe, in [his] heart, that if this had happened in a more affluent, not majority-minority community the state [would have] ever let it get this far.” Carl S. Taylor, a sociology professor at the Michigan State University and ethnographer of poor communities, stated, “it’s both a class and race issue. When you have companies there, they dump everything into the water and into poor communities.”

Communities of color have consistently less access to healthy foods and environments, including temperature regulation in extreme weather. As the environment further deteriorates, this will only become more true. The prices for fresh foods go up every year and it becomes more and more difficult for people in low income communities to have options in their diet outside of fast food and items available in local corner stores.

Climate change is stacked against people of color through the lack of funding for protection and action in lower income communities and yet, this is rarely recognized publicly. However, as the fight to protect our environment gets more and more attention, advocacy for people of color’s unique position in the environment is growing. This movement is being championed by youth.

UPROSE, an organization that provides a platform for youth empowerment, hosts an annual Climate Justice Youth Summit, which brings together hundreds of young people in the pursuit of racial justice and the nurturing of our environment. This summit “creates opportunities for young people of color to lead teach-ins, trainings, art builds, and more as a way to build an authentic climate justice movement that’s culturally and artistically attuned to the lives of young people.” Last year, they held a fashion show that began a discussion on the intersection of culture, class, labor laws, fashion, and nature.

Many Indigenous youth across North America have become outspoken about climate justice and the ways in which they, as native people and youth living in an industrialized world, experience the intersection of colonialism and climate change. Quite an expansive amount of Indigenous Nations reside on the frontline and have “contaminated soil, open-air wastewater pits and poisoned water sources.” Indigenous youth are speaking out at conferences across the country to make the intentional placement and degradation of their land visible.

Nineteen percent of Congress identifies as non-white. This means that the current Congress is the most racially diverse that it’s ever been in U.S history. However, these numbers remain low and the climate justice movement in the government remains lacking. With a current Republican majority house, the bills that fight for climate justice-related topics are rarely passed. In the 115th Congress, 52 of the 100 members of the Senate and 232 of the 435 members of the House of Representatives are reported climate change deniers. Of the 179 bills revolving climate change that have been introduced since January, only one has been enacted. This bill was put in place to lighten the effects of coal mining on the environment. With a president who maintains the stance that climate change is a non-issue, the presence of racial justice within that movement is severely lacking. For this reason, citizens may have to be the ones to make the push for more public recognition of the racial and socioeconomic intersections in environmental justice.

Climate change is not just an environmental issue, but also “a social justice issue,” says Lawrence Palinkas, the Albert G. and Frances Lomas Feldman Professor of Social Policy and Health at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work. If we refuse to treat it this way, then we will be unable to understand or resolve the myriad of problems that people of color and people in poverty experience daily. Peaceful Uprising, an organization supporting climate justice says, “Fixing an interconnected world demands [an] interconnected movement” of people fighting to address “environmental degradation and the racial, social, and economic inequities it perpetuates.”