"Respectability politics are never straightforward, but they are complicated even more by the history of black people in the U.S. and the carnal need to survive, even if that means abandoning morality."

-- Leila Mottley

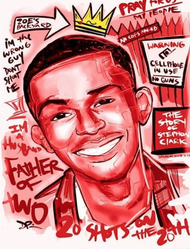

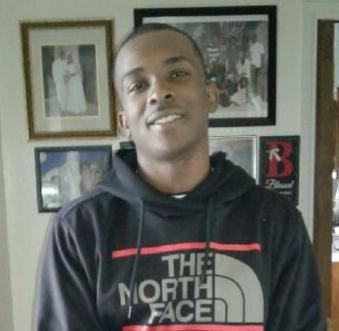

Stephon Clark was fatally shot by police in his grandmother’s backyard in Sacramento on March 18th, 2018 when trying to enter through the back door. The body camera footage quickly went viral and the Black Lives Matter movement organized protests in his honor.

Not long after Clark’s murder, misogynistic tweets of his were uncovered ranging from “dark bitches bring dark days” to “birthday next month, all I want is my baby and my bitch [...] you want me? Just feed me.” All of these tweets led to the same denigration of black women and fetishization and degradation of other women.

Respectability politics have been present in the U.S., especially in black culture, since slavery. The term refers to the ways in which marginalized groups attempt to visibly show alignment with mainstream culture, in pursuit of respect. During slavery, this was a survival method in order to have some facade of control over punishment.

Respectability politics in the modern black community refer to the idea that if a black person’s behavior is in alignment with white norms, then they will be able to not only survive, but be successful (in the workplace, at school, etc.). Often, respectability politics are perpetuated within the marginalized community as a reflection of the internalization of these norms.

When speaking to police violence and Black Lives Matter, respectability politics are central and far more sensitive. It is easy to reduce a person to a flaw or even to one decision or trait. We see this in our daily political divide as we instinctively reduce others to what feels most important. However, in terms of black public figures this becomes even more complex as some people wish to erase any flaws from public discussion, while others wish to reduce the individuals to simply these flaws.

As Clark’s posthumous tweets gained media coverage, many people instinctively felt repulsed by Clark’s misogyny and disrespect of black women, and sought to remove him from the public image of Black Lives Matter. Journalist Talia Leacock says in an opinion article, “[Clark’s] misogynoir has made defending him difficult.” As emotional beings, we want our political beliefs to line up with our personal beliefs; in this case, Leacock was personally offended by his comments, while still believing that Clark did not deserve to die and that, politically, we need to advocate for him.

The controversy around Clark prompts us to think about the importance of separating what we feel about a person’s attitude from what we feel about a person’s existence. Leacock goes on to take the stance that “as foul and harmful as misogynoir may be, it is not a crime punishable by death."

Just because many have come to this conclusion, it does not mean that everyone believes Clark should continue to be a martyr in the black community. This is where respectability politics come into play: if we cannot respect (some aspects of) the person, can we respect the politics they represent? Can we respect their right to exist or to be successful?

Respectability politics have been present in the U.S., especially in black culture, since slavery. The term refers to the ways in which marginalized groups attempt to visibly show alignment with mainstream culture, in pursuit of respect. During slavery, this was a survival method in order to have some facade of control over punishment.

Respectability politics in the modern black community refer to the idea that if a black person’s behavior is in alignment with white norms, then they will be able to not only survive, but be successful (in the workplace, at school, etc.). Often, respectability politics are perpetuated within the marginalized community as a reflection of the internalization of these norms.

When speaking to police violence and Black Lives Matter, respectability politics are central and far more sensitive. It is easy to reduce a person to a flaw or even to one decision or trait. We see this in our daily political divide as we instinctively reduce others to what feels most important. However, in terms of black public figures this becomes even more complex as some people wish to erase any flaws from public discussion, while others wish to reduce the individuals to simply these flaws.

As Clark’s posthumous tweets gained media coverage, many people instinctively felt repulsed by Clark’s misogyny and disrespect of black women, and sought to remove him from the public image of Black Lives Matter. Journalist Talia Leacock says in an opinion article, “[Clark’s] misogynoir has made defending him difficult.” As emotional beings, we want our political beliefs to line up with our personal beliefs; in this case, Leacock was personally offended by his comments, while still believing that Clark did not deserve to die and that, politically, we need to advocate for him.

The controversy around Clark prompts us to think about the importance of separating what we feel about a person’s attitude from what we feel about a person’s existence. Leacock goes on to take the stance that “as foul and harmful as misogynoir may be, it is not a crime punishable by death."

Just because many have come to this conclusion, it does not mean that everyone believes Clark should continue to be a martyr in the black community. This is where respectability politics come into play: if we cannot respect (some aspects of) the person, can we respect the politics they represent? Can we respect their right to exist or to be successful?

Historically (and presently), the media has a troubled track record of reducing black victims to their perceived negative traits. In a New York Daily News report release March, 2017 about a black victim killed by a white supremacist, the journalist described the perpetrator as “dapper” and described the victim by listing his arrest record and saying he was “menacing.” In the September, 2018 killing of Botham Shen Jean, a black man, in his Dallas, TX apartment, the media chose to emphasize the marijuana they found in his apartment.

Black death is consistently overshadowed by the negative depiction of black life. In response to this pattern, many Black Lives Matter supporters have taken a “don’t speak ill of the dead” stance, referring to the recognition of his misogyny as “slander.”

Black death is consistently overshadowed by the negative depiction of black life. In response to this pattern, many Black Lives Matter supporters have taken a “don’t speak ill of the dead” stance, referring to the recognition of his misogyny as “slander.”

The “don’t talk about it” philosophy is not specific to victims of police violence. This attitude is common to the way many people view black figures in general, ranging from Barack Obama to Beyoncé.

Beyoncé is an icon in both music and the black community. Her fame has surpassed love or appreciation and become a symbol for black women as flawless human beings. While the (beyond physical) beauty of black women is a much needed narrative, Beyoncé has become another figure that is reduced to perfection. There was even a Saturday Night Live skit that consisted of a parody of a “fake movie trailer, ‘The Beygency,’ [depicting] what happens to a man who dares to speak a not-entirely-worshipful way about Beyoncé.”

When Barack Obama won the presidency, most black people were elated. This elation remained consistent even as he made decisions in his terms that many progressive black people would otherwise not agree with. Obama deported more people than any other president and ordered the dropping of thousands of bombs in the Middle East. Despite all of this, there is a common stance among black people that he must be seen as a flawless leader.

This “rule” of worship for black figures in the U.S. is born out of the fear that by introducing narratives of the flawed black figure, the public will let those flaws overshadow their positive qualities—or even worse, be used as justification for their death. Black people often feel that any complaint is going to be “viewed as complicity with wrong, harm and evil,” Michael Eric Dyson wrote, explaining black views of President Barack Obama.

Dyson says, “the often unconscious feeling seemed to be that [Obama] survived the worst they could do to him, and the fact that they haven’t killed him means that everything else he does is a bonus.” If this is true, then does that mean black people who don’t survive are exempt from accountability because the only important thing is black death?

All three of these people have presented some appeal to white culture or internalization of white norms. Stephon Clark’s remarks about black women play into the common narrative that black women are undesirable. President Obama continually “downplay[s] his Blackness to appease the white moderates and white independents.” Even Beyoncé has spent the majority of her career trying to alter her image to be accessible by a white audience. Recently, she has abandoned this, saying, “I have worked very hard to get to the point where I have a true voice [...] and at this point in my life and my career, I have a responsibility to do what’s best for the world and not what is most popular.”

Yet, even when black figures attempt to align themselves with white culture, black people continue to defend them with no room for discussion. Maybe this is because black people would rather have some figure in the limelight, even a one-dimensional one, than risk losing all black mainstream representation by calling anyone out. Or perhaps it is because black people know that the way people view black figures will undoubtedly reflect the way they are viewed. Or maybe it is simply an internalization that we must respect and celebrate white norms.

Beyoncé is an icon in both music and the black community. Her fame has surpassed love or appreciation and become a symbol for black women as flawless human beings. While the (beyond physical) beauty of black women is a much needed narrative, Beyoncé has become another figure that is reduced to perfection. There was even a Saturday Night Live skit that consisted of a parody of a “fake movie trailer, ‘The Beygency,’ [depicting] what happens to a man who dares to speak a not-entirely-worshipful way about Beyoncé.”

When Barack Obama won the presidency, most black people were elated. This elation remained consistent even as he made decisions in his terms that many progressive black people would otherwise not agree with. Obama deported more people than any other president and ordered the dropping of thousands of bombs in the Middle East. Despite all of this, there is a common stance among black people that he must be seen as a flawless leader.

This “rule” of worship for black figures in the U.S. is born out of the fear that by introducing narratives of the flawed black figure, the public will let those flaws overshadow their positive qualities—or even worse, be used as justification for their death. Black people often feel that any complaint is going to be “viewed as complicity with wrong, harm and evil,” Michael Eric Dyson wrote, explaining black views of President Barack Obama.

Dyson says, “the often unconscious feeling seemed to be that [Obama] survived the worst they could do to him, and the fact that they haven’t killed him means that everything else he does is a bonus.” If this is true, then does that mean black people who don’t survive are exempt from accountability because the only important thing is black death?

All three of these people have presented some appeal to white culture or internalization of white norms. Stephon Clark’s remarks about black women play into the common narrative that black women are undesirable. President Obama continually “downplay[s] his Blackness to appease the white moderates and white independents.” Even Beyoncé has spent the majority of her career trying to alter her image to be accessible by a white audience. Recently, she has abandoned this, saying, “I have worked very hard to get to the point where I have a true voice [...] and at this point in my life and my career, I have a responsibility to do what’s best for the world and not what is most popular.”

Yet, even when black figures attempt to align themselves with white culture, black people continue to defend them with no room for discussion. Maybe this is because black people would rather have some figure in the limelight, even a one-dimensional one, than risk losing all black mainstream representation by calling anyone out. Or perhaps it is because black people know that the way people view black figures will undoubtedly reflect the way they are viewed. Or maybe it is simply an internalization that we must respect and celebrate white norms.

Just like Beyoncé represents the possibility of black life with perfect absolutism, “martyrs” like Stephon Clark represent the possibilities for black death with clean absolutism. President Obama is consistently backed up by the black community (more than 90% support from black people) with all flaws dismissed. In the end, there seems to be an instinct to protect black figures under attack by the white world and leave out any faults on their part.

Respectability politics are never straightforward, but they are complicated even more by the history of black people in the U.S. and the carnal need to survive, even if that means abandoning morality.

Respectability politics are never straightforward, but they are complicated even more by the history of black people in the U.S. and the carnal need to survive, even if that means abandoning morality.