"GEntrification is hard topic to talk about, especially because of how differently it affects different people in their communities. To completely understand gentrification and everything that comes with it, we have to look at how everyone is affected." -- Maya Mastropasqua, 7th grade

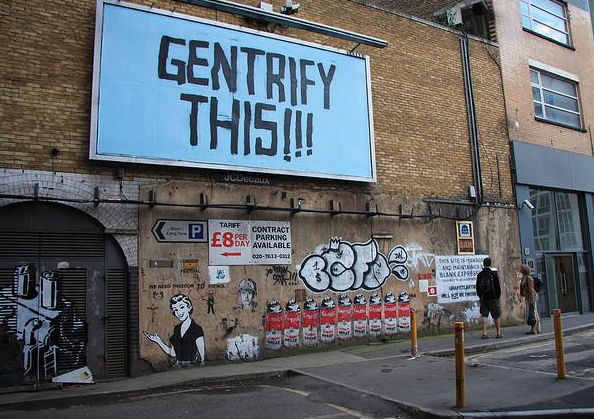

Gentrification and housing in the Bay Area and California is a big and long-lasting problem with so many complexities. While there are many benefits, including communities becoming wealthier, there’s also many downsides, including people being pushed out of their homes, a disproportionate amount of those people being minorities. Although it's hard to completely understand, we can try.

What is gentrification? “A neighborhood that has previously been under-invested in, maybe hasn’t had as many resources, maybe the rents are cheaper, and they don’t have as many amenities,” answers Oakland resident Ann Catrina-Kligman. In other words, gentrification is when poorer neighborhoods change from rents moving up, and wealthier people moving in, often times leading to the pre-existing residents to be pushed out.

Looking in on gentrification last year, the article Gentrification and Disinvestment 2020, by Jason Richardson, Bruce Mitchell, and Jad Edlebi on the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), reports a study done on Opportunity Zones and highly gentrifying places. “We identified 954 neighborhoods with indications of gentrification in the period 2013-2017,” the article states, explaining the study they conducted. “These were concentrated in 20 ‘intensely gentrifying’ metro areas,” they further explained, “The top cities for intensity of gentrification during the period are San Francisco-Oakland, Denver, Boston, Miami, and New Orleans.”

Another Oakland resident, Sharron Glenn notes the study when discussing her stance on gentrification, saying, “I’m in the middle, I understand both sides of it. And I know that San Francisco and Oakland from 2013 to 2017 or 2018 were one of the top 20 cities in the U.S. for gentrification which is kind of crazy. The pro and con side of it depends on where you're coming from, whether you're living in the respective city and your subject to it or benefiting from it, it just depends on how that plays out.”

The NCRC article also mentions how race always comes into effect. With minorities usually being the overwhelming population of those being pushed out, which can be seen through their study, “The average minority population of the neighborhoods included in this study was 50%, but that figure rose to 77% in areas we determined to have gentrified,” they record.

As neighborhoods gentrify, we also see the atmosphere change. Catrina-Kligman talked about the new dynamics brought in from gentrification that she witnesses, “What I’ve noticed is as there’s been higher-end restaurants, and condos, and apartments that have moved in, I’ve also noticed that the homelessness has increased. I know the area where OSA is, and if I compare it now to what it was like 10 years ago, it looks very different and I notice the same thing in Temescal. I see more homlessness, but there’s also a Whole Foods getting ready to open,”` she says.

Further discussing what Catrina-Kligman briefly mentioned on homelessness, Glenn says, “There is a huge increase in the amount of displaced folks, many of which are victims of the pandemic, many of which are victims of mental illness. So homelessness has increased, probably at least ten fold.”

The Teen Vogue article, “What Is Gentrification? How It Works, Who It Affects, and What To Do About It,” written by Andrew Lee delves into the differences and complexities of gentrification. It compares both sides of the argument of whether or not gentrification is beneficial to cities and communities. The article uses one article by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and another by a trio of professors at NYU to argue the side of gentrification being better for residents.

“[the article] found that city dwellers move frequently for a multitude of reasons, and changes can increase quality of life and educational attainment for neighborhood children.” Lee cites. For the against gentrification argument Lee references Jean Anyon’s book Radical Possibilities. He writes, “[the book] describes a successful community school reform campaign in Chicago’s Logan Square that inadvertently created a situation where “housing values rise, businesses increasingly invest in the neighborhood, and low-income residents are pushed out by higher rents.”

A lot of times an idea can be construed that anti-gentrification activists don’t want poorer communities to have better tools, and nicer houses. But Lee shuts this idea down writing, “It’s not that anti-gentrification activists are against nice things for their communities; these organizers say the problem is that often these nice things aren’t actually designed for them, but for their replacements — like a boutique that professionals new to the area can afford to patronize.”

To the point of activists against gentrification frustrations the article discusses gentrification's possible effect in the tragic death of Breonna Taylor in March of last year. “She was a Black woman living in a gentrifying neighborhood,” the article says. Dezmond Goff, of Seattle’s Black Frontline Movement, even told Teen Vogue, “They increased police presence because that was one way [to break up the neighborhood.] If we incarcerate more people we can break up community that way, we can get people out that way.”

Communities being stripped of its diversity and what makes them “special” is a notable side effect. Catrina-Kligman talked about how saddening it is for her to see that change, “One of the things I love about Oakland is, there’s so many different cultures represented. So you can get Ethiopian food or go to a great taqueria, there’s just all this variety and I feel like oftentimes when those small neighborhood establishments start disappearing and you just get American food.”

A former worker for the department of housing development and now working on sustainable regional planning, Josh Geyer discussed the complexities of gentrification. Geyer starts by defining what gentrification really is. “A new population of higher income or higher socioeconomic status starts moving into a formerly lower income lower socioeconomic status neighborhood and as a result the neighborhood starts to change in ways that make the original residents feel alienated and unwelcome,” he explains. In recent years gentrification has steadily gotten worse. “Gentrification is partly a result of housing costs being so high, so housing costs are getting worse and worse in general, and that goes for everywhere in the Bay Area, and that includes neighborhoods that are vulnerable to gentrification,” he explains, “The fact that housing prices overall are accelerating upwards makes that process of gentrification accelerate as well.”

There are a lot of mixed opinions when it comes to gentrification, and it can become hard to tell how much gentrification really impacts. When asked how big of a problem gentrification really is when it comes to housing he said, “There is not enough housing and the result is that the housing that exists is too expensive. To me that is the platform of everything else that is all happening. That is underneath the gentrification the people see and experience in their communities.”

Geyer also talks about how big gentrification really is, how far back it goes, and its racist roots. “The neighborhoods that are most often subject to gentrification pressure, gentrification risk, are neighborhoods that were formerly and currently segregated, disinvested neighborhoods. So these are neighborhoods where all the black people had to live because they literally weren’t allowed to live anywhere else. Because there’s a prejudice against black individuals and black communities, those communities have been undervalued systematically, forever,” he says.

The big root of the problem, of course, is the lack of housing. With more people than houses, it’s inevitable that we end up with homelessness. “In the Bay Area, in California we’re around two and half million houses short of what we need for our current population. In fact, California stopped growing in population very recently. Purely because we don’t have enough housing,” Geyer says.

But, our current answer to the problem isn’t the perfect answer for everyone. He explains, “You segregate people, you disinvest in their neighborhoods, that’s racist, period. If you're reversing that process, you’d think it’s gotta be anti racist. But change is hard and change causes disruption and change causes discomfort. So people are like ‘why should I have to go through discomfort and disruption after having this whole horrible history of discrimination. And I don’t think there’s a good answer to that.”

Through time, and with change, neighborhoods turn over, and a lot of cities, especially here, become wealthier and more heavily invested in. However, there is also a lot of displacement that comes from this. It’s hard to understand the right way to support people and their houses and communities, we should just start by being informed of what’s going on around us.

What is gentrification? “A neighborhood that has previously been under-invested in, maybe hasn’t had as many resources, maybe the rents are cheaper, and they don’t have as many amenities,” answers Oakland resident Ann Catrina-Kligman. In other words, gentrification is when poorer neighborhoods change from rents moving up, and wealthier people moving in, often times leading to the pre-existing residents to be pushed out.

Looking in on gentrification last year, the article Gentrification and Disinvestment 2020, by Jason Richardson, Bruce Mitchell, and Jad Edlebi on the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), reports a study done on Opportunity Zones and highly gentrifying places. “We identified 954 neighborhoods with indications of gentrification in the period 2013-2017,” the article states, explaining the study they conducted. “These were concentrated in 20 ‘intensely gentrifying’ metro areas,” they further explained, “The top cities for intensity of gentrification during the period are San Francisco-Oakland, Denver, Boston, Miami, and New Orleans.”

Another Oakland resident, Sharron Glenn notes the study when discussing her stance on gentrification, saying, “I’m in the middle, I understand both sides of it. And I know that San Francisco and Oakland from 2013 to 2017 or 2018 were one of the top 20 cities in the U.S. for gentrification which is kind of crazy. The pro and con side of it depends on where you're coming from, whether you're living in the respective city and your subject to it or benefiting from it, it just depends on how that plays out.”

The NCRC article also mentions how race always comes into effect. With minorities usually being the overwhelming population of those being pushed out, which can be seen through their study, “The average minority population of the neighborhoods included in this study was 50%, but that figure rose to 77% in areas we determined to have gentrified,” they record.

As neighborhoods gentrify, we also see the atmosphere change. Catrina-Kligman talked about the new dynamics brought in from gentrification that she witnesses, “What I’ve noticed is as there’s been higher-end restaurants, and condos, and apartments that have moved in, I’ve also noticed that the homelessness has increased. I know the area where OSA is, and if I compare it now to what it was like 10 years ago, it looks very different and I notice the same thing in Temescal. I see more homlessness, but there’s also a Whole Foods getting ready to open,”` she says.

Further discussing what Catrina-Kligman briefly mentioned on homelessness, Glenn says, “There is a huge increase in the amount of displaced folks, many of which are victims of the pandemic, many of which are victims of mental illness. So homelessness has increased, probably at least ten fold.”

The Teen Vogue article, “What Is Gentrification? How It Works, Who It Affects, and What To Do About It,” written by Andrew Lee delves into the differences and complexities of gentrification. It compares both sides of the argument of whether or not gentrification is beneficial to cities and communities. The article uses one article by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and another by a trio of professors at NYU to argue the side of gentrification being better for residents.

“[the article] found that city dwellers move frequently for a multitude of reasons, and changes can increase quality of life and educational attainment for neighborhood children.” Lee cites. For the against gentrification argument Lee references Jean Anyon’s book Radical Possibilities. He writes, “[the book] describes a successful community school reform campaign in Chicago’s Logan Square that inadvertently created a situation where “housing values rise, businesses increasingly invest in the neighborhood, and low-income residents are pushed out by higher rents.”

A lot of times an idea can be construed that anti-gentrification activists don’t want poorer communities to have better tools, and nicer houses. But Lee shuts this idea down writing, “It’s not that anti-gentrification activists are against nice things for their communities; these organizers say the problem is that often these nice things aren’t actually designed for them, but for their replacements — like a boutique that professionals new to the area can afford to patronize.”

To the point of activists against gentrification frustrations the article discusses gentrification's possible effect in the tragic death of Breonna Taylor in March of last year. “She was a Black woman living in a gentrifying neighborhood,” the article says. Dezmond Goff, of Seattle’s Black Frontline Movement, even told Teen Vogue, “They increased police presence because that was one way [to break up the neighborhood.] If we incarcerate more people we can break up community that way, we can get people out that way.”

Communities being stripped of its diversity and what makes them “special” is a notable side effect. Catrina-Kligman talked about how saddening it is for her to see that change, “One of the things I love about Oakland is, there’s so many different cultures represented. So you can get Ethiopian food or go to a great taqueria, there’s just all this variety and I feel like oftentimes when those small neighborhood establishments start disappearing and you just get American food.”

A former worker for the department of housing development and now working on sustainable regional planning, Josh Geyer discussed the complexities of gentrification. Geyer starts by defining what gentrification really is. “A new population of higher income or higher socioeconomic status starts moving into a formerly lower income lower socioeconomic status neighborhood and as a result the neighborhood starts to change in ways that make the original residents feel alienated and unwelcome,” he explains. In recent years gentrification has steadily gotten worse. “Gentrification is partly a result of housing costs being so high, so housing costs are getting worse and worse in general, and that goes for everywhere in the Bay Area, and that includes neighborhoods that are vulnerable to gentrification,” he explains, “The fact that housing prices overall are accelerating upwards makes that process of gentrification accelerate as well.”

There are a lot of mixed opinions when it comes to gentrification, and it can become hard to tell how much gentrification really impacts. When asked how big of a problem gentrification really is when it comes to housing he said, “There is not enough housing and the result is that the housing that exists is too expensive. To me that is the platform of everything else that is all happening. That is underneath the gentrification the people see and experience in their communities.”

Geyer also talks about how big gentrification really is, how far back it goes, and its racist roots. “The neighborhoods that are most often subject to gentrification pressure, gentrification risk, are neighborhoods that were formerly and currently segregated, disinvested neighborhoods. So these are neighborhoods where all the black people had to live because they literally weren’t allowed to live anywhere else. Because there’s a prejudice against black individuals and black communities, those communities have been undervalued systematically, forever,” he says.

The big root of the problem, of course, is the lack of housing. With more people than houses, it’s inevitable that we end up with homelessness. “In the Bay Area, in California we’re around two and half million houses short of what we need for our current population. In fact, California stopped growing in population very recently. Purely because we don’t have enough housing,” Geyer says.

But, our current answer to the problem isn’t the perfect answer for everyone. He explains, “You segregate people, you disinvest in their neighborhoods, that’s racist, period. If you're reversing that process, you’d think it’s gotta be anti racist. But change is hard and change causes disruption and change causes discomfort. So people are like ‘why should I have to go through discomfort and disruption after having this whole horrible history of discrimination. And I don’t think there’s a good answer to that.”

Through time, and with change, neighborhoods turn over, and a lot of cities, especially here, become wealthier and more heavily invested in. However, there is also a lot of displacement that comes from this. It’s hard to understand the right way to support people and their houses and communities, we should just start by being informed of what’s going on around us.