When people think of the classic coming of age film, the works of ‘80s filmmaker John Hughes come to mind. Whether it be a group of ragtag teens finding kinship in detention or a high school senior skipping school and singing “Twist and Shout” on a parade float, the teen movies of the decade have become iconic narratives of adolescence.

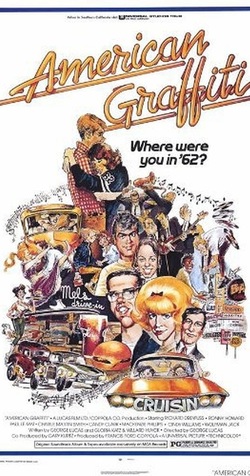

Promotional poster for American Grafitti

Promotional poster for American Grafitti Thirty years later, the same movies are watched by teens today. However, the coming-of-age genre has changed drastically. The 2010s is a decade dominated by movies that depict dystopic adolescents, like in the massively successful Hunger Games (2012) and Divergent (2014) series. If they’re not dealing with some sort of apocalypse or dictatorship, then teens are dealing with inner turmoil like depression, drug abuse, or even cancer as depicted in The Fault in Our Stars (2014). Today, teen films harbor a more serious tone than the movies that came before. How did the genre get to this point? And what does this say about the real life teen experience for Generation Z?

Arguably, George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973) is the perfect archetype for a coming-of-age movie. American Graffiti follows a group of teens in 1962 during their last night in town before leaving for college and the beginning of their adult lives. This movie has it all: romance, insecurity, and uncertainty. Despite the characters grappling with life changes,the film is lighthearted and fun. American Graffiti is upbeat as it moves from scenes at the school dance to kids drinking beer, smoking cigarettes, and driving all night long. Although the viewer wonders if the central couple will break up and if another character will make up his mind about going off the college the next morning, the endearing tone of the film comforts the viewer and allows us to trust the judgment of the teens: we believe that everything is going to be alright. This comfort allows us relate to the film, because we feel safe with its characters, almost as if we’re hanging out with them in 1962.

Jeff Spicoli, a lovable stoner played by Sean Penn.

Jeff Spicoli, a lovable stoner played by Sean Penn. In the ‘80s, coming of age films dealt with heavier topics, but still maintained the idea of classic adolescent fun. In Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), the main female becomes pregnant near the end of the film and decides to get an abortion. Here, we see teen films become more serious, as her character was someone who strived for male approval so much that it led to her be dissatisfied with love, and unhappy in general. However, the weight of her narrative is balanced by Sean Penn’s character, Jeff Spicoli, a perpetually stoned student who is strongly disliked by his history teacher. This equilibrium makes the movie relatable to a broader scope of people, and while it does allow us to think about the fragile self esteem that comes with being a teen, we are also able to laugh and not get bogged down in our emotions.

A scene near the end of The Breakfast Club where the teens find out each other's insecurities.

A scene near the end of The Breakfast Club where the teens find out each other's insecurities. This trend of equilibrium in teen films continued throughout the ‘80s. In The Breakfast Club (1985), we get glimpses into the complex lives of five students in Saturday detention while laughing at the sharp dialogue and watching organic friendships develop between people who seemed nothing alike. In Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986), Ferris's best friend, Cameron, is clearly depressed, and Ferris is using his “day off” as a way to hold onto the little amount of time he has left to enjoy being a carefree teenager before he leaves for college.

Dazed and Confused (1993) started off the ‘90s coming of age genre in a similar fashion to American Graffiti, but with extremely low stakes. Set in 1976, Dazed and Confused has almost no plot. We are literally watching the characters on an average night for them like in American Graffiti. All they do is ride around town, smoke weed, drink, harass younger kids, and meet up with friends. Their biggest worries are not being able to get Aerosmith tickets and not being able to both play football and be able to party. The movie is so fluid and organic that it perfectly captures the essence of being young and dumb.

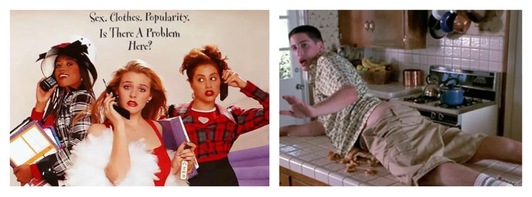

Left: Promotional poster for Clueless. Right: A scene from American Pie where a teenage boy has sex with an apple pie.

Left: Promotional poster for Clueless. Right: A scene from American Pie where a teenage boy has sex with an apple pie. However, the rest of the teen movies of the ‘90s did not follow that carefree, hang-out archetype. Films like Clueless (1995), Ten Things I Hate About You (1999), and American Pie (1999), looked at the teen years from a comedic, almost satirical angle. The stakes are entirely around social status: How do I get the popular boy to notice me? What should I wear to look cool? I need to lose my virginity before prom or else I’m a loser! These themes were prominent in teen films of the past, but in the ‘90s and early 2000s, they were exaggerated so the viewer could see some of the absurdity of teenage priorities.

As the 2000s progressed, teen films diversified. The Harry Potter franchise (2001-2011) became very, very popular, setting the stage for coming of age within the fantasy genre. Alternatively, independent teen films began to focus on quirk and awkwardness. The sleeper hit Napoleon Dynamite (2004) and cult classic Juno (2007) epitomize those two qualities. Napoleon Dynamite's slow dialogue, iconic cadence, and life context are so weird that we can’t take our eyes off of him. We connect to Napoleon, but we can’t exactly pinpoint how. In Juno, the story of a teenage girl who gets pregnant and decides to keep the child to term, it is the title character’s aloofness to her situation and her unique personality that let us see life through her strange lens. Humor, particularly the crude and campy variety, was still important to the coming of age genre as shown through the success of George Mottola's Superbad (2007), but it did not have the same influence over films as it did before.

Scene from Palo Alto where the characters ditch a part to go to a nearby graveyard one of their classmates is buried in.

Scene from Palo Alto where the characters ditch a part to go to a nearby graveyard one of their classmates is buried in. That brings us to the 2010s. At the beginning of the decade, dystopia became the new teen film. People rushed to theaters to watch Katniss Everdeen fight tyranny, help others, and fall in love in the Hunger Games trilogy. If your film did not have magic, destruction, or a moderately attractive love interest, no one was going to see it. Because of this, more and more coming of age movies were made independently. In these films, teens deal with very serious life issues such as sexual abuse, depression, and drug abuse--sans comic relief. These films lack the equilibrium of their 80s predecessors. In James Franco’s Palo Alto (2013) and Marielle Heller's Diary of a Teenage Girl (2015), the characters engage in reckless behavior in an attempt to “find themselves.” In both films, adult men prey on young girls. Now, we are expected to watch the character struggle, with no guarantee of a complete resolution. Teen life, as portrayed through these films, became gritty and cynical, instead of carefree and ignorant.

The change in teen movies could arguably be due to a change in culture. In the 80s, when coming of age movies were at their peak, CEO’s and big movie companies realized that teens were a viable market. Because of this, heavy marketing towards adolescents was prevalent throughout the decade, specifically in media like movies and music. In order to satisfy the demand for teen content, movies about youth were being churned out constantly. Over time, that aggressive teen marketing in movies faded and became more concentrated in other areas, such as clothing, television shows, and social networks. Less demand for teen movies led to less being made, let alone to be shown in theaters all across America.

Some believe that this generation of young people is more cynical and distressed than the generations that came before. With more education and less stigma around mental illness and sexuality, more teens today are informed and vocal about their personal strife and want to see that reflected in the media they consume. In the '80s, teens wanted to see their lives idealized, and movie companies complied. Today, we acknowledge that youth is not just about sex and sneaking out of the house to hang out with friends. Young people deal with very real issues, and society is at a point where is as acceptable to portray the darker side of growing up.

All in all, the teen movie is a central part of American culture. Because of them, we are able to get a clear representation of youth throughout history. Perhaps as the teens of Generation Z become adults, we will bring the teen movie back into the mainstream and give the younger generation modern representations of youth they can connect with instead of having to travel back fifty years to find themselves in film. Not to knock the work of the late great John Hughes, but as society continues to develop, our movies need to develop as well. The modern teenager needs their Ferris Bueller, too.

Some believe that this generation of young people is more cynical and distressed than the generations that came before. With more education and less stigma around mental illness and sexuality, more teens today are informed and vocal about their personal strife and want to see that reflected in the media they consume. In the '80s, teens wanted to see their lives idealized, and movie companies complied. Today, we acknowledge that youth is not just about sex and sneaking out of the house to hang out with friends. Young people deal with very real issues, and society is at a point where is as acceptable to portray the darker side of growing up.

All in all, the teen movie is a central part of American culture. Because of them, we are able to get a clear representation of youth throughout history. Perhaps as the teens of Generation Z become adults, we will bring the teen movie back into the mainstream and give the younger generation modern representations of youth they can connect with instead of having to travel back fifty years to find themselves in film. Not to knock the work of the late great John Hughes, but as society continues to develop, our movies need to develop as well. The modern teenager needs their Ferris Bueller, too.