It’s not only on the big screen that we see racist denialism by way of “the black friend” cliche. Time and time again, we see white individuals using the black people in their lives as social retribution for their own racist tendencies.

-Sunari W-a

It is 1990, and among the Best Picture Nominees for the Academy Awards is Driving Miss Daisy. A movie based on the fantasy of an impossible relationship in Jim Crow-era Atlanta, in which an elderly white woman overcomes her racist tendencies and befriends her black driver. In the Oscar cycle for last year’s movies, came a film with a similar premise, in reverse: a white driver overcoming his racism and befriending his black passenger. Like its predecessor, Green Book emerged from the night with several Oscar wins, among them the Academy Award for Best Picture. However, what these wins - nearly 30 years apart - make evident is that the popular mythos of racial reconciliation is still appealing to moviegoers. It becomes a problem when it conceptually alters how we think about racial tension on a interpersonal, and even national level.

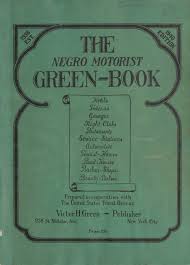

Green Book tells the story of Don Shirley, a renowned black pianist, and Frank Anthony Vallelonga (aka Tony Lip), the Italian-American man hired to drive him across the deep south to various gigs. The movie’s namesake is The Negro Motorist’s Green Book, written by Victor Hugo Green in the 1930’s, a travel guide for black Americans, allowing them to safely navigate their routes. The title of the movie suggests that Tony Lip was Don Shirley’s green book, a symbolism that undoubtedly robs Shirley’s character of agency.

Green Book tells the story of Don Shirley, a renowned black pianist, and Frank Anthony Vallelonga (aka Tony Lip), the Italian-American man hired to drive him across the deep south to various gigs. The movie’s namesake is The Negro Motorist’s Green Book, written by Victor Hugo Green in the 1930’s, a travel guide for black Americans, allowing them to safely navigate their routes. The title of the movie suggests that Tony Lip was Don Shirley’s green book, a symbolism that undoubtedly robs Shirley’s character of agency.

According to the movie’s writer and Tony Lip's son Nick Vallelonga, this is the story as Don Shirley told him. That Dr. Shirley - a moniker stemming from his honorary doctorates - gave direct instructions on how to tell the story, and that if a biopic of sorts should arise, to write it posthumously. However, Shirley’s brother, Maurice Shirley, dismissed the truthfulness of the film, calling it a “symphony of lies.” Various kin claim that this movie was an erasure of Shirley, as a musician, a father, a brother and a black man.

There are various moments in the film where Lip saves Shirley from racially charged altercations, and several where his estranged relationship with his blackness and his family are addressed. Shirley’s nephew, Edwin Shirley, says that he was all but disconnected from the black community. He references his friendships with other prominent black artists - Duke Ellington, Nina Simone and Sarah Vaughan - and his activity in the civil rights movement - his participation in Selma for instance. In response to the film, Dr. Maurice Shirley, Don Shirley’s brother, wrote that “if the motive was to tell a true and authentic story, either about ‘The Green Book’ and/or Donald Shirley, they clearly missed the mark.”

Wesley Morris of The New York Times recently wrote an essay in which he details the racial reconciliation trope in relation to Green Book and countless other films - The Blind Side, The Help, Les Intouchables. He argues that when interracial relationships are affected by racism, “prolonged exposure to the black half of the duo enhances the humanity of [the] white, frequently racist counterpart.” This truth becomes even more troubling when the same phenomena is referenced off-screen.

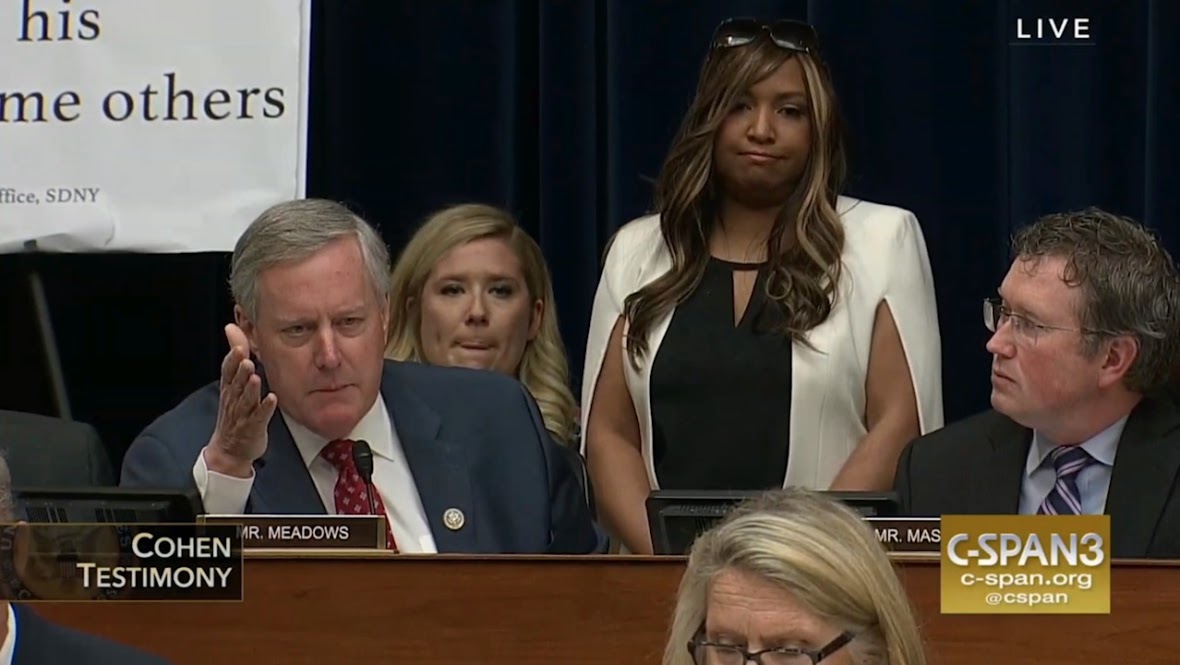

This mythos recently presented itself to us again, this time in the highly-anticipated political episode that was Michael Cohen’s congressional hearing. In two separate fiascos, North Carolina Representative Mark Meadows uses proximity to a person of color to eliminate the possibility of a person’s racism - for both himself and Donald J. Trump. While defending Cohen’s accusations of racism in the White House, Meadows brings up Lynna Patton, a Trump family aide, HUD official and black woman, to stand behind him. He announces that “as a daughter of a man born in Birmingham, Alabama, that there is no way that [Patton] would work for an individual who was racist.” He proceeded to speak on her behalf, at which point, Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib called him out for using Patton as a prop, and that doing so, was a racist act. He immediately cited his “grandchildren of color” as a defense for why he was immune from being a perpetrator of such racism.

There are various moments in the film where Lip saves Shirley from racially charged altercations, and several where his estranged relationship with his blackness and his family are addressed. Shirley’s nephew, Edwin Shirley, says that he was all but disconnected from the black community. He references his friendships with other prominent black artists - Duke Ellington, Nina Simone and Sarah Vaughan - and his activity in the civil rights movement - his participation in Selma for instance. In response to the film, Dr. Maurice Shirley, Don Shirley’s brother, wrote that “if the motive was to tell a true and authentic story, either about ‘The Green Book’ and/or Donald Shirley, they clearly missed the mark.”

Wesley Morris of The New York Times recently wrote an essay in which he details the racial reconciliation trope in relation to Green Book and countless other films - The Blind Side, The Help, Les Intouchables. He argues that when interracial relationships are affected by racism, “prolonged exposure to the black half of the duo enhances the humanity of [the] white, frequently racist counterpart.” This truth becomes even more troubling when the same phenomena is referenced off-screen.

This mythos recently presented itself to us again, this time in the highly-anticipated political episode that was Michael Cohen’s congressional hearing. In two separate fiascos, North Carolina Representative Mark Meadows uses proximity to a person of color to eliminate the possibility of a person’s racism - for both himself and Donald J. Trump. While defending Cohen’s accusations of racism in the White House, Meadows brings up Lynna Patton, a Trump family aide, HUD official and black woman, to stand behind him. He announces that “as a daughter of a man born in Birmingham, Alabama, that there is no way that [Patton] would work for an individual who was racist.” He proceeded to speak on her behalf, at which point, Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib called him out for using Patton as a prop, and that doing so, was a racist act. He immediately cited his “grandchildren of color” as a defense for why he was immune from being a perpetrator of such racism.

Screen grab of C-SPAN's broadcast of the Micheal Cohen hearing

It’s not only on the big screen that we see racist denialism by way of “the black friend” cliche. Time and time again, we see white individuals using the black people in their lives as social retribution for their own racist tendencies. If life imitates art, it’s vital that these relationships cease to be romanticized in film.

Life is not Green Book. Racial tensions hardly blossom into friendships and they rarely end in mutual understanding. The necessity of a Negro Motorist’s Green Book illustrates that. From “sundown towns” (violently segregated municipalities), to a rise in racially charged hate crimes in the last two years. It’s unrealistic to assume proximity will dissolve these historic, systematic tensions. It’s only through communication, information and recognition that that cultural ignorances can truly begin to dissolve.

Life is not Green Book. Racial tensions hardly blossom into friendships and they rarely end in mutual understanding. The necessity of a Negro Motorist’s Green Book illustrates that. From “sundown towns” (violently segregated municipalities), to a rise in racially charged hate crimes in the last two years. It’s unrealistic to assume proximity will dissolve these historic, systematic tensions. It’s only through communication, information and recognition that that cultural ignorances can truly begin to dissolve.