"THERE ARE TWO KINDS OF TATTERS: TATTOO ARTISTS, AND LACE MAKERS." -NASEEM ALAVI

There are two kinds of tatters: tattoo artists, and lace makers. Lacis Museum in Berkeley, is currently hosting an exhibition on the latter form. This Saturday, I had the opportunity to meet and interview two of the artists, Andrea Brewster and Yuuko Terachi, who have their work on display.

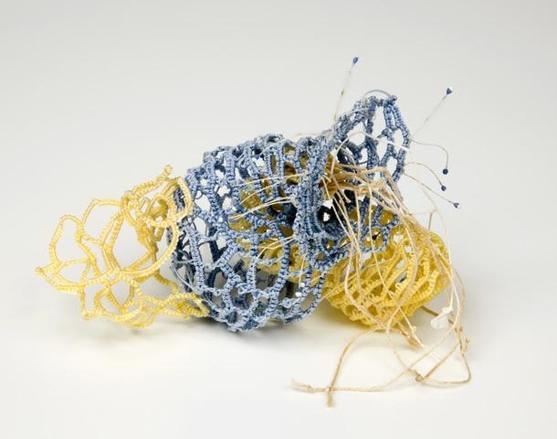

Andrea Brewster lives in Oakland and specializes in hyperbolic tatting, a three-dimensional form of lace using scientific algorithms to create small sea-creature like sculptures. Yuuko Terachi lives in Kyoto, Japan. She is the last living master of an old form of tatting cultivated in Japan during the Taisho Era (1912-1926) that uses three tatting shuttles and beads to create ornate jewelry and objects.

For a long time, Terachi had a great fear of airplanes and was unable to travel. Anyone who wanted to meet her or learn from her talents had to fly thousands of miles. However, she recently overcame her anxiety in order to give a talk in Oakland this September and meet the other tatting artists, as well as to spread the word of her particular art form. In preparation for the three-day trip, she went so far as to cut her hair from shoulder-length to a spiky bob, because she felt it would be easier to take care of while travelling. Terachi has over a hundred students who fly from all over Japan to have lessons with her about once a month.

Tatting Demonstration By Yuuko Terachi

Tatting Demonstration By Yuuko Terachi Terachi learned these tatting techniques from her teacher who learned it in high school during the Taisho Era. Her teacher had many students, but most quickly dropped out of her rigorous training program until only Terachi and two other students were left. Now she is the only one left alive of these three.

“I commuted from Kyoto to Tokyo every month for thirteen years,” Terachi said. “But I still felt as though I hadn’t learned anything.”

Because her teacher made her promise not to share the craft, she had to wait until her teacher passed away to begin teaching her own students. Even now, her talent isn’t fully recognized because of the age-associated hierarchy in Japan, which prevents her from officially having the authority to teach.

“I commuted from Kyoto to Tokyo every month for thirteen years,” Terachi said. “But I still felt as though I hadn’t learned anything.”

Because her teacher made her promise not to share the craft, she had to wait until her teacher passed away to begin teaching her own students. Even now, her talent isn’t fully recognized because of the age-associated hierarchy in Japan, which prevents her from officially having the authority to teach.

Tatting Shuttles

Tatting Shuttles Tatting is typically created by making a series of two-part knots, called double stitches. These are made using a small pod-shaped instrument called a tatting shuttle. Tatting shuttles are about three inches long, traditionally made out of ivory or metal. Terachi’s shuttles are custom made at a local factory from clear plastic. Unfortunately, the machinery at the company where she orders her shuttles has broken, and the company decided it wasn’t worth the money to fix it. Now, this company uses a new kind of machine that makes thinner shuttles. These thinner shuttles break more easily, so their customers will have to come back for more, increasing revenue.

American tatter, Andrea Brewster, has taken advantage of 3D printing technology to craft her own shuttles. She models the shuttle in a program called Rhino and sends them to Shapeways 3D printing company. “There are lots of shuttles that do the job,” Brewster said. “But to have one that’s beautiful enhances the process of making something that’s beautiful as well.”

American tatter, Andrea Brewster, has taken advantage of 3D printing technology to craft her own shuttles. She models the shuttle in a program called Rhino and sends them to Shapeways 3D printing company. “There are lots of shuttles that do the job,” Brewster said. “But to have one that’s beautiful enhances the process of making something that’s beautiful as well.”

However, with the invention of tatting, such ornaments became obtainable for middle class women as well. “Most people’s response to tatting is either that they’ve never heard of it, or that it’s fiddly and old fashioned,” she said. “With my work, I’m trying to bring something new to the conversation.”

Andrea Brewster’s artistic career has taken many forms. She won a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts for a series of drawings of lace with handwriting where she wrote the text to various fairytales. After starting a family, her focus shifted toward tatting, through which she explores gender traditions and class.

Andrea Brewster’s artistic career has taken many forms. She won a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts for a series of drawings of lace with handwriting where she wrote the text to various fairytales. After starting a family, her focus shifted toward tatting, through which she explores gender traditions and class.

In the 19th century, lace was only available to the upper class. However, with the invention of tatting, such ornamentations became obtainable for middle class women as well. “Most people’s response to tatting is either that they’ve never heard of it, or that it’s fiddly and old fashioned,” Brewster said. “With my work, I’m trying to bring something new to the conversation.”

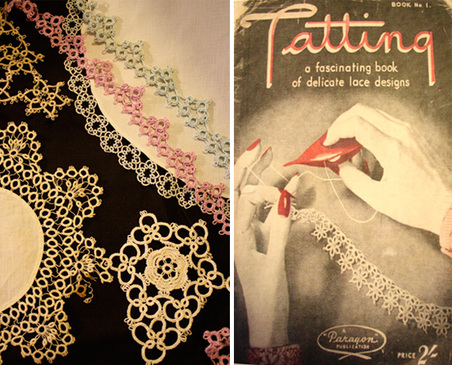

Tatting reached its peak in the late 1800s in Europe as an alternative to lace making. It was primarily used for doilies and to embellish clothing. It was an easy pass time for upper class women to do while gossiping. Some people say it grew out of an earlier technique called knotting, which was also used to embellish clothing.

Japanese Cherry Blossom Doily

Japanese Cherry Blossom Doily In Japan, tatting was introduced by Christian missionaries in the late 1800s. There were special secondary schools for women to learn refined art forms and etiquette. When the missionaries were given permission to teach in schools, they included tatting in the curriculum for young women. It became one of the things that every cultured woman in Japanese society had to know. As a result, many Japanese women in their 80’s know how to tat.

“It’s not often that there are large displays of tatting,” Brewster explained. “Except for a few conferences that happen every few years. I think this is the first time that a museum has put together an exhibition on tatting.”

Both artists were very pleased with the outcome of the show and getting to share traditions, exchange techniques, and spread their art form. Brewster’s tatting is on the sculptural and artsy spectrum of tatting, while Terachi's work leans towards functional tatting. By coming together, they create a well rounded show, covering the full spectrum from historical to contemporary tatting and is on view until April 2017. The Museum is located at 2982 Adeline Street in Berkeley at the corner of Ashby Ave and across the street from the Ashby Bart Station. Hours are Monday through Saturday 12:00-6:00pm.

http://lacismuseum.org/exhibit/Tatting/

“It’s not often that there are large displays of tatting,” Brewster explained. “Except for a few conferences that happen every few years. I think this is the first time that a museum has put together an exhibition on tatting.”

Both artists were very pleased with the outcome of the show and getting to share traditions, exchange techniques, and spread their art form. Brewster’s tatting is on the sculptural and artsy spectrum of tatting, while Terachi's work leans towards functional tatting. By coming together, they create a well rounded show, covering the full spectrum from historical to contemporary tatting and is on view until April 2017. The Museum is located at 2982 Adeline Street in Berkeley at the corner of Ashby Ave and across the street from the Ashby Bart Station. Hours are Monday through Saturday 12:00-6:00pm.

http://lacismuseum.org/exhibit/Tatting/